A Christmas Gift for President Lincoln

The period of November 15th through December 21st, 2014, marks the 150th anniversary of Major General (and native Ohioan) William Tecumseh Sherman’s Savannah Campaign—also known as the “March to the Sea.” From the captured city of Atlanta, Georgia, Sherman launched a scorched earth military strategy which led to the destruction of military and civilian targets alike. Sherman’s orders were clear: “forage liberally”; “destroy mills, houses, cotton-gins, &c.” in areas in which “guerillas and bushwhackers molest our march [or] inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local hostility”; and “appropriate freely and without limit” horses, mules, wagons and other belongings.

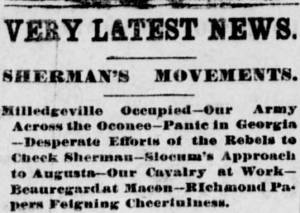

Across the nation, civilians read of Sherman’s campaign in their local newspapers. Opinions on the success—and justness—of the campaign varied from paper to paper and from state to state. The Lancaster Gazette,from Sherman’s hometown, stated that “[his] programme in Georgia…will startle the public” and be “one of the most extraordinary campaigns of the war” (November 17, 1864, Image 2, col. 7).

Some of the news printed in Ohio papers was borrowed from Southern papers that were much closer to the action. On November 29, 1864, a few days after Milledgeville, Georgia, had fallen, the Cleveland Morning Leader copied items from several Richmond, Virginia, papers. The Whig of that city reported that that while there was no definite news from Georgia, they thought Sherman would head toward the coast without attacking Augusta. If he “really attempted so wild a movement,” the paper declared, “his expedition will come to grief” (Image 2, col. 4). The Whig went on to say, “We do not understand precisely why it is that the Yankees go into ecstacies of delight and admiration over Sherman’s movement, unless it be that they are bound to consider themselves the greatest and smartest people in creation.” Reports from the North painted Sherman’s progress in a more positive light, and on December 30, 1864, a week after the campaign had ended, the Delaware Gazette reported that “General Sherman’s triumphant march…met no serious opposition, and his army ‘fared sumptuously every day’…without any loss of men or material on his side” (Image 2, col. 1).

The truth of his campaign lay somewhere between these two extremes, but after only a month, Georgia and the Confederacy had been devastated. Hundreds of miles of railroad tracks and telegraph lines were destroyed; numerous bridges and cotton mills and gins were wrecked; some 22,000 horses, mules and cattle were seized; and 20 million pounds of food were taken. When he reached Savannah, Sherman left the city untouched, demanding and receiving its surrender. He presented it as a Christmas gift to President Abraham Lincoln and he and his troops rested there through the holiday until it was time to start the next and final campaign of the Western Theater of the Civil War through the Carolinas.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Thanks to Jenni Salamon, Coordinator for the Ohio Digital Newspaper Program, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.