Garrett Morgan Saves the Day

What do gas masks and water tunnels have in common? That would be Garrett Morgan!

On July 24, 1916, in an underground tunnel beneath Lake Erie, four miles out from Cleveland, a construction crew encountered a terrible accident. Stumbling across a natural gas pocket, a sudden explosion in the middle of the night injured, killed, and buried several workers. As the gas filled the tunnel, the initial rescuers succumbed to the toxic fumes and their fate below ground. Ten of them died.

The Cleveland police department rang on Garrett Augustus Morgan, “the inventor of Harlem Avenue.” Known for his multiple inventions, he was called up near four in the morning, urged to bring as many of his recently patented “safety hoods” as possible!

Morgan’s safety hoods covered the entire face and connected to long, filtered tubes that dangled low near the ground. As hot smoke and fumes rose in the air, cleaner air below could be breathed more safely—and filtered more effectively—through the mask’s tubes.

Garrett Morgan called his brother, Frank, and with his neighbor William Roots and other volunteers, loaded his car with 20 of his helmets and rushed to the scene. Garrett, Frank, and two volunteers descended to retrieve the fallen rescuers: although ten had already died, they carried out the rest.

Having demonstrated the effectiveness of the hood, the rescue began in earnest. Throughout the night and early morning, rescuers, now donned in Morgan’s protective equipment, dug out the remaining survivors of the explosion.

Garrett Morgan’s safety hood was later refined during WWI, in conjunction with other designs, to create a similar device for which he is generally credited: the gas mask.

Interestingly, the water intake crib—to which the tunnel headed—works under the same principle as Morgan’s safety hood. By installing a water intake pump four miles off shore into the lake, the polluted waters near the shore could be avoided, taking in fresher water to be pumped back into the city. It’s unknown (and unlikely) that Morgan took inspiration from this—he marketed the safety hood mostly to fire departments. However, the coincidence that his invention should rescue the laborers working to achieve the same purpose is too noteworthy for me to exclude in this blog post!

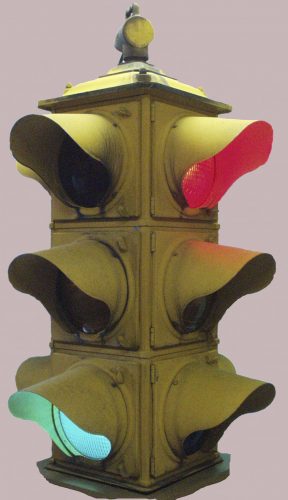

And to wrap up, here’s your bonus question: what do a gas mask and a traffic light have in common? No, Garrett Morgan didn’t use his safety hood to rescue people from automobile accidents. He invented the three-part traffic signal instead! His patent, one of the first to use a visual warning signal between “go” and “stop” was sold to the General Electric Company in 1923. Previous designs may have used an audible warning, which may have been hard to hear, had they been installed in a busy city like Cleveland.

Among Garrett A. Morgan’s many other achievements include: starting the G.A. Morgan Hair Refining Company, which sold hair straighteners and other hair care products; starting a sewing machine repair shop; later, with his wife Mary, a clothing store called Morgan’s Cut Rate Ladies Clothing Store; and helping to found the Cleveland Association of Colored Men. He even has a children’s book based on his life, entitled Redlight, Greenlight, written by Dovie Sweet. It can be paged from our collections (and has some cool illustrations, to boot).

He is, however, perhaps most known for his bravery and heroics that night at the Cleveland waterworks, and for his genius that saved the survivors there.

Works cited:

Jim Dubelko, “The 1916 Waterworks Tunnel Disaster,” Cleveland Historical, accessed July 28, 2021, https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/736.

“Colored Hero at Cleveland Disaster” The monitor. (Omaha, Neb.), 05 Aug. 1916. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/00225879/1916-08-05/ed-1/seq-1/>

“Descendants of Cleveland’s 1916 Waterworks Tunnel disaster meet for the first time” https://www.cleveland.com/metro/2016/07/descendants_of_clevelands_1916.html

Garrett A. Morgan Historical Marker. https://remarkableohio.org/index.php?/category/309

Thank you to Jen Cabiya, Digital Projects Coordinator at the Ohio History Connection, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.