A Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa: The Journal of Hugh Clapperton

The late 19th century was the beginning of a period of renewed European imperialism, specifically the Race for Africa. The Race for Africa refers to the competition between European nations over control of Africa and its resources, which ended in the division of the continent among the competing colonizing nations. In many cases, explorers were sent to collect information and report back to the motherland, and Hugh Clapperton, an Englishman, was one such explorer.

Clapperton was born in Annan, Dumfriesshire, in 1788. He lacked a traditional education but still learned to read and write. At a young age, he was sent to study with a man named Bryce Downie, a mathematician who would be especially helpful in teaching Clapperton navigation and trigonometry. When he turned thirteen, Clapperton left Downie to join the crew of his first vessel. He spent the next several years serving on multiple different ships before an interest in visiting Africa was piqued by Dr. Walter Oudney. In time, he set off on a couple trips to satisfy this newfound curiosity, but this post will cover only one of those trips.

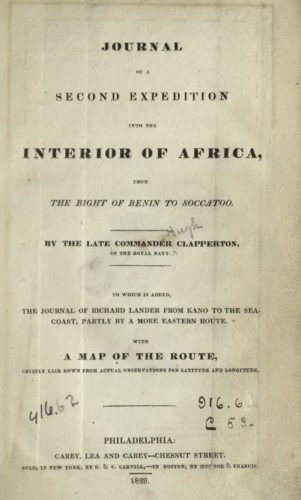

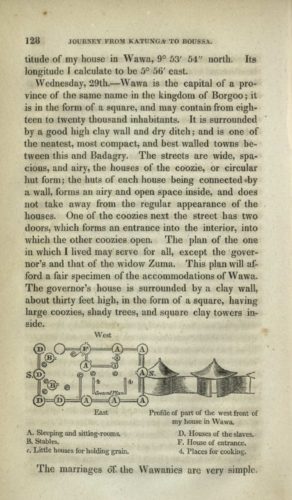

During his second trip, Clapperton kept a journal, known as the Journal of a Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa, detailing his travels around the region of Sudan. While the journal possesses multiple instances of insignificant facts, there are some interesting tidbits that can be gleaned. Clapperton recorded his interactions with residents of the different villages he visited, describing their behavior and cultural norms. His notes can help a reader realize characteristics, such as the polygamous nature of some 19th century African societies or the settings in which villages were situated. One may also note the emphasis that was placed on slavery and the reverence with which the African king of Eyeo was treated.

This is not all, however–a picture emerges of how Clapperton himself viewed the African men and women he encountered, as well. For instance, on more than one occasion, he described them as “civil,” a characterization that almost makes it seem as though Clapperton expected to be met by barbarians. However, the reader is free to draw his or her own conclusions. Overall, he appeared to view the Africans he met in a positive light, engaging in conversations to learn about their culture and even utilizing their medicinal remedies.

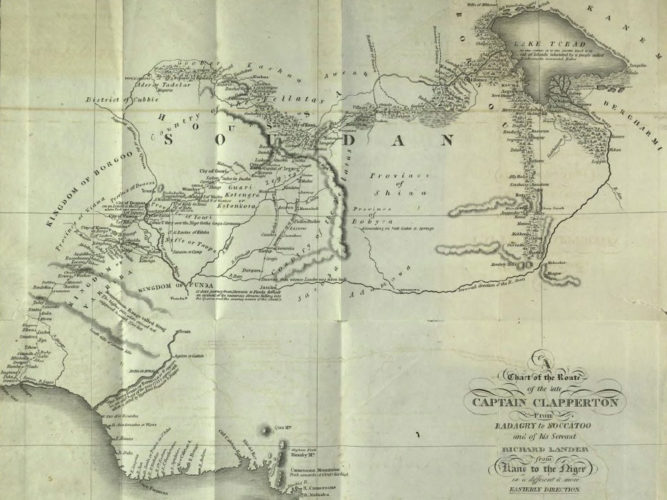

For any who wish to look through a copy of this journal, you need not look further than the State Library of Ohio. A copy rests in the Rare Books room but can also be found on Ohio Memory for those seeking more convenient access. The journal includes a section from Clapperton’s servant, Richard Lander, who describes his own experiences during the expedition and the events following his master’s death. The introduction also includes letters between Lander, Clapperton, and others, as well as a map of Sudan that can be found at the front of the book. The map is meant to capture the route Clapperton and his fellow travelers took as they made their way across Sudan. Thus, the reader can follow Clapperton’s progress as they progress through the journal. For any person with an interest in historic accounts of exploration, and a European perspective of western and central Africa during the 19th century, this is a story that cannot be missed.

Thank you to Desmond Bolden for this week’s post! Desmond is a senior History major at Kent State University with a planned graduation date of December 2018. He spent several months as an intern at the State Library of Ohio, and now plans for a career in librarianship.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.