Ohio’s “Minute Men”: Squirrel Hunters and the Defense of Cincinnati

Ohioans are familiar with many of the most notable battles of the Civil War–we have learned about Gettysburg, Antietam, Chickamauga and more since we first studied the conflict in school. But have you ever heard of the Squirrel Hunters?

In early September of 1862, the Civil War was in its second year, and Confederate forces were on the move northward. Southern troops under General Kirby Smith were able to capture Lexington, Kentucky; Smith then dispatched General Henry Heth to capture nearby Covington, Kentucky, as well as the city of Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River– an effort which, if successful, would be the first invasion of Confederates into Ohio. In response to the fall of the last line of Union defense in the area, Major General Horatio Wright, commander of Union forces in Kentucky, ordered General Lewis Wallace to prepare Covington’s and Cincinnati’s defenses.

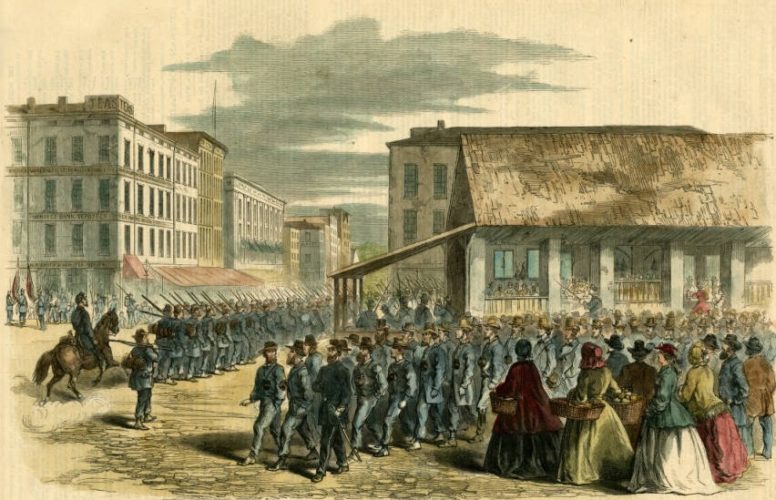

Once in Cincinnati, Wallace moved quickly to declare martial law, and at the same time issued a call in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan for a volunteer militia. Local business owners were ordered to close their shops, and civilians to report for military duty in defense of the Ohio border, preparing defensive features like trenches in order to ready the two towns for attack. Ohio Governor David Tod left Columbus and came to Cincinnati to assist Wallace, ordering Ohio’s adjutant-general to send any available troops not currently guarding Ohio’s southern border, and for the state quartermaster to send 5,000 guns to equip Cincinnati’s militia. A number of Ohio counties offered their men for the defense of Cincinnati as well, an offer which Tod immediately accepted on Wallace’s behalf. He stated that only armed men should report, and that transport should be provided by railroads at no cost. The state of Ohio would later cover the bill. Civilians from 65 counties–a total of over 15,000 men–converged on Cincinnati as part of a volunteer militia that would soon become known as the “Squirrel Hunters.”

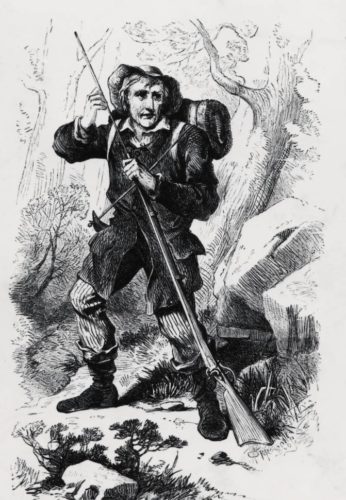

Many of these men had no previous military experience, and the weapons they brought were outdated–more suited to small game hunting than combat, and thus the source of their enduring nickname. A 1915 article from the Amherst Weekly News characterizes the men’s weapons as “pitchforks, clubs and pistols and blunderbusses of the vintage of 1812 or thereabouts.” Churches, meeting halls, warehouses, and even Cincinnati’s Fifth Street Markethouse were commandeered to operate as makeshift barracks and dining halls as men crowded in to come to the city’s defense.

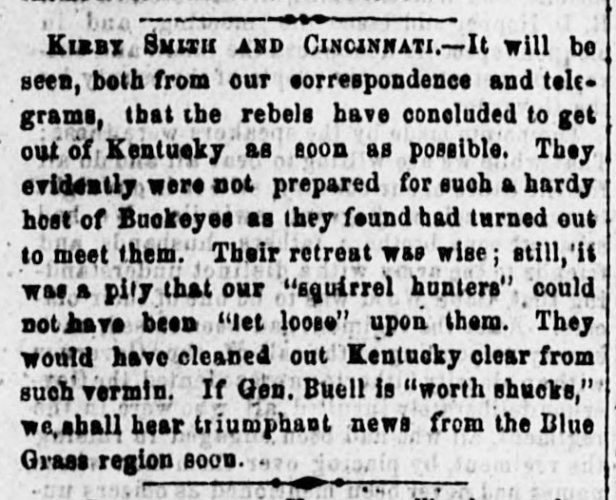

Between volunteer defenders and the regular army, Heth’s men reported a force of 70,000 along the border, and the Southern advance was quickly and effectively repelled without direct conflict or bloodshed. A Confederate scout is reported to have said of the volunteers, “They call them Squirrel Hunters; farm boys that never had to shoot at the same squirrel twice.” Wallace quickly lifted martial law, and allowed all businesses to reopen (with the exception of those that sold alcoholic beverages). By September 13th, Cincinnati got word that enemy forces were withdrawing and the town was no longer in danger. Thanks to the bravery and willingness to serve of thousands of everyday Ohioans under the leadership of Tod and Wallace (henceforth nicknamed the “Savior of Cincinnati”), Cincinnati and Covington were saved from Confederate control.

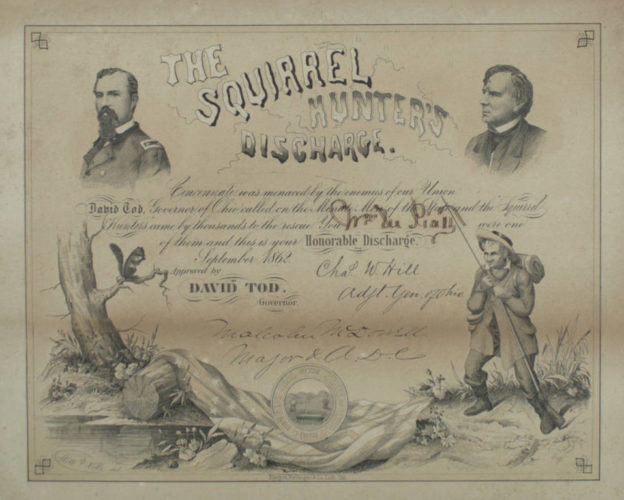

Without much fuss, the Squirrel Hunters returned to their homes and livelihoods, although newspapers of the time like the Mt. Vernon Democrat suspected that they may be called up to assist again before long. The following year, as a show of thanks, the Ohio legislature authorized funds for Governor Tod to print discharges for these men from military duty. To this end, Tod issued a call for each county to furnish the names of the men who volunteered as Squirrel Hunters, stating in part, “The people of the State owe a debt of deep gratitude to the ‘Squirrel Hunters,’ who, by their prompt response to the call made upon them, saved the cities and towns upon the southern border from the fire and sword of the enemies of our glorious government.” Examples of these discharges can be found on Ohio Memory, with numerous other examples in the archival holdings of the Ohio History Connection.

Further recognition would come in 1908, when the Ohio General Assembly passed a resolution to pay each surviving Squirrel Hunter (a surprising number, according to the Wooster Daily News) a stipend of $13, equal to one month’s pay for an Ohio militiaman in 1862. Want to know more? You can learn about the interesting story of Ohio’s Squirrel Hunters on Ohio Memory as we remember their contribution to our state’s history and their impact on the Civil War.

Thanks to Lily Birkhimer, Digital Projects Coordinator at the Ohio History Connection, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.