“Believe That I Still Remain, Benjamin Lundy,” Part I

We live in a glorious Republic (sneer) we boast a free Press (sneer) We are all on grounds of equal enjoyment — sneer — None subjected to the domineering tyranny of our own kith & kin! Sneer! Deluded visionaries — reverse the Phantasmagorean picture + judge of the true grounds on which you stand Where is our boasted Republic of 76!

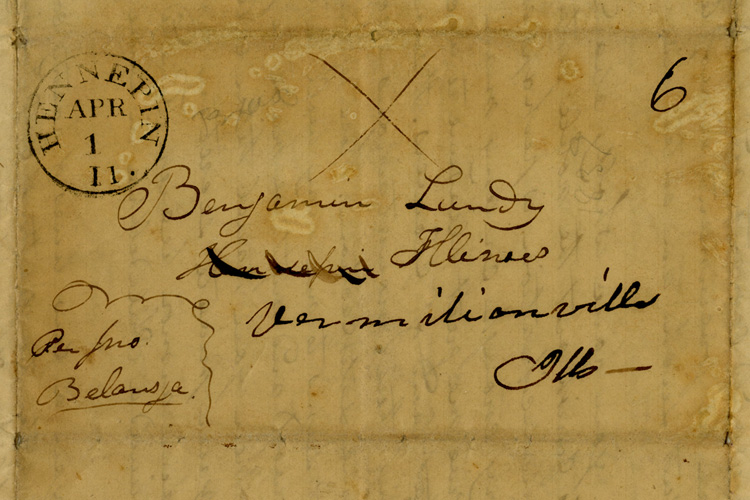

So declared one anonymous early-19th century North Carolina abolitionist in a letter to his peers. This letter — amongst a host of other correspondence, legal documentation and travel writing — makes up the Benjamin Lundy Papers, held by the Ohio History Connection, and recently added to Ohio Memory. The collection charts not only the sentiments and career of path-breaking early abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, but constellates Lundy’s work and reception within the larger context of the U.S. anti-slavery movement at the time.

Born in New Jersey, Benjamin Lundy (1789-1839) was a prominent Quaker abolitionist who developed strong ties to Ohio, and became best known for his development of abolitionist periodicals. His most famous anti-slavery periodical, the Genius of Universal Emancipation, was first published in 1821 from his home in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio, and enjoyed a wide circulation across the antebellum United States. In the 1820s, the young William Lloyd Garrison came to work for The Genius. Benjamin Lundy traveled widely seeking subscriptions to The Genius, giving talks about the anti-slavery movement, and observing and documenting the conditions of enslaved people across the Americas. He was also involved in the establishment of freed slave colonies in Mexico, and was widely remembered as one of the first generation of pioneering U.S. anti-slavery advocates in the Jacksonian Age.

The Benjamin Lundy Papers provide a remarkable window onto Lundy’s life and times. They include not only Lundy’s correspondence with his friends and family on political topics, but also a series of land and legal contracts with the government of Tamaulipas, Mexico, where Lundy and his friends hoped to establish a colony for freed slaves. These documents in particular shed light on understandings and negotiations around the U.S.-Mexico border zones in the years before the Texas Revolution and Mexican-American War. Moreover, the Lundy materials give a sense of the diverse sentiments surrounding anti-slavery movements in Ohio and neighboring states at the time; and they wed the public face of anti-slavery activism with private correspondence, from Lundy and others, on matters of family and home. Documents in the collection range from euphoric and missionary in tone to charting the loneliness and rage of early abolitionists.

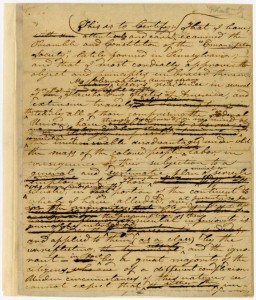

The collection contains a heavily-edited draft of one of Lundy’s anti-slavery tracts –- perhaps in preparation for inclusion in the Genius or on one of Lundy’s many abolitionist speaking engagements –- and also includes two remarkable travelogues, detailing Lundy’s travels through Michigan and along the Ohio River, and through Texas and Louisiana. Lundy traveled these many miles on foot, on horseback, and on boats ranging from coal vessels to Mississippi steamboats to observe the conditions of enslaved Americans across the U.S., and to spread the word about his Genius of Universal Emancipation.

These travelogues, written in Lundy’s distinctive staccato voice, are full of rich topographical, botanical and cultural observation, and are punctuated throughout with Lundy’s piercing observations on everyday perspectives on slavery in the 1820s. Lundy’s extensive travels throughout Ohio, including stops in cities and towns ranging from Tiffin to Zanesville to Marietta to Gallipolis to Hamilton to Cincinnati, bring a unique eye to social life and culture in Ohio during the early period of statehood. But despite the seriousness of his mission, Lundy’s travels through Ohio and beyond were also not without humor. At one point on a journey, Lundy recounts an unwilling bedfellow he meets at a wagon camp:

26th — Go on at daylight — pitch pine timbered country — good road — hot travelling — Fort Jessup [sic], 24 miles from where I lodged last night — go 2 miles further — encamp with some wagoners — shower creep under wagon — large dog dispute the occupancy of that place with me! — kept my ground, tho !! –

Tune in next Friday for Part II of our blog post exploring the newly-available Lundy Papers. Thank you to Jess Lamar Reece Holler for this week’s post! Jess is a graduate student in the Department of Folk Studies & Anthropology at Western Kentucky University who is interningwith the Ohio History Connection.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.