A History of Juneteenth

As Juneteenth, now a federal holiday, approaches, we wanted to take this opportunity to revisit our post from June 2020 about its origins and history.

The story of Juneteenth is an essential part of the history of the Civil War. During the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation made slavery’s demise one of the North’s principal war aims. But in the beginning, few Northerners or Southerners thought the conflict was about slavery. Southerners contended that the war was the result of the federal government’s refusal to respect the rights of the states. Northerners argued that the federal government had to protect and preserve the Union.

President Abraham Lincoln also sought only to preserve the United States. Lincoln refused to end slavery during 1861 and the first half of 1862 for several reasons. First, he believed that the United States Constitution prevented the president from seizing the property—enslaved Africans—of a citizen without due process. Second, Lincoln didn’t want to alienate the residents of slave states that had remained in the Union. These included Kentucky, Missouri, Delaware, and Maryland. If these states joined with the South, thousands of more men would join the Confederacy. Lincoln wanted to solidify the North’s control over these slave-holding states. Third, Lincoln realized that many Southerners and Northerners would not support the end of slavery because it would pave the way for African American equality. Finally, Lincoln worried that ending slavery would alienate any Union sympathizers currently in the South, further strengthening the Confederacy.

But by the summer of 1862, Lincoln had become convinced that slavery had to end. Northern troops had firm control over the Border States. Lincoln was convinced that any Union support in the Confederacy would not persuade secessionists to rejoin the United States. And a growing number of Northerners began to believe that slavery was morally wrong. As Northern soldiers marched into the South, many of these men saw the real brutality of slavery for the first time. These soldiers wrote to their loved ones in the North about the injustice, prompting calls for the end of slavery.

Eventually, Lincoln decided that the federal government did have the right to hamper the South’s ability to wage war. He reasoned that the Constitution allowed the president to adopt measures during times of war to help guarantee a military victory. Lincoln decided that ending slavery would diminish the Confederate war effort, making his actions legal under the United States Constitution.

Lincoln drafted an initial version of the Emancipation Proclamation in July 1862, but he did not issue it to the public until September 22, 1862. Lincoln believed that U.S. citizens and other nations might negatively view his action unless some Union victories preceded it. Following the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, Lincoln finally had a critical Union victory in the east.

Ohioans greeted the Emancipation Proclamation differently. Radical Republicans, like Senator Benjamin Wade, welcomed the document, as did Ohio’s abolitionists and Quakers. Others, especially those from working-class backgrounds, were not as welcoming. Many feared that Blacks would flee the South, move to Northern states, and take jobs away from White working people. Some Ohioans serving in the Union military refused to fight a war to end slavery, so they deserted and returned home.

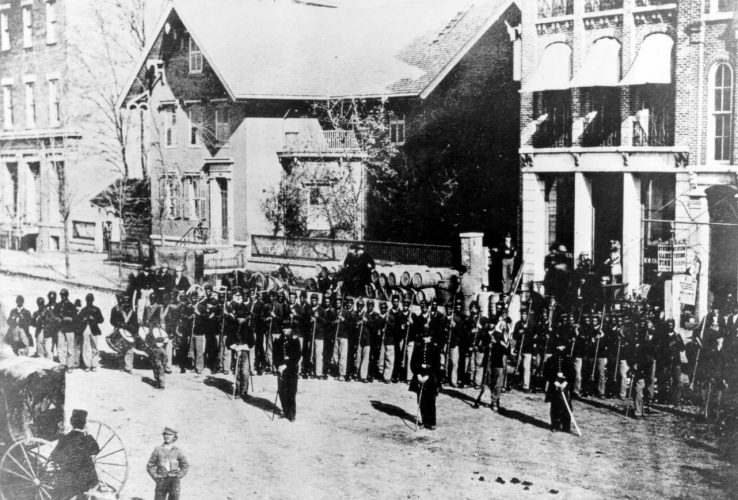

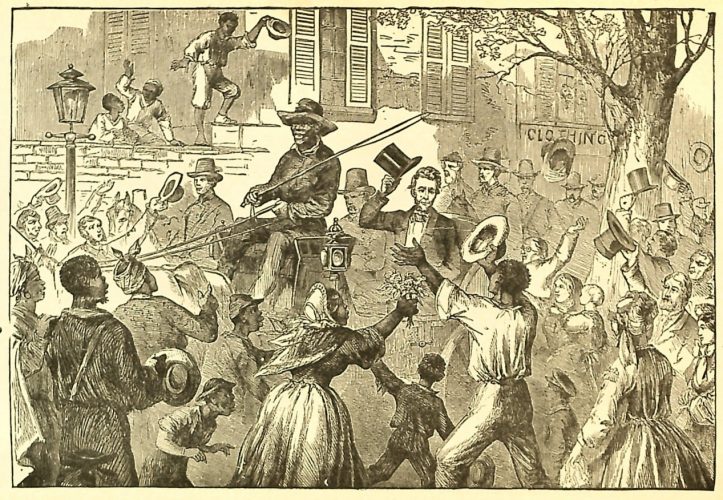

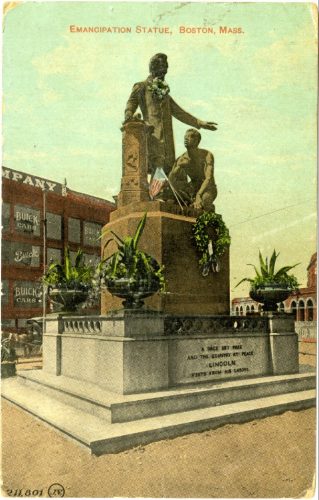

The Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the Border States or in areas in the South that Union forces had conquered. Slavery did not end everywhere in the United States until the passage of the 13th amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865. However, the news about the 13th amendment did not reach many southern plantations. Soon after the war, the state of Texas itself abolished slavery on June 19, 1865. On that day, there were still enslaved African Americans in Galveston and other cities. When Union General Gordon Granger came to Galveston to enforce the emancipation, word spread quickly, and a celebration ensued. Today, all 50 states recognize Juneteenth as an official American holiday.

To this day, the holiday is celebrated as Freedom Day or Juneteenth Independence Day by many African Americans. The National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center (NAAMCC) and the Ohio History Connection are celebrating this year with a slate of events and programs. You can see the full schedule here, including information about the 1890s-style Jubilee Day Festival at Ohio Village and Juneteenth ON THE AVE on Columbus’ Historic Mt. Vernon Avenue. Each year, the NAAMCC celebrates Juneteenth to ensure that all Ohioans remember what it means to African Americans and the history of our entire country.

Juneteenth represents one of the first steps toward equality for enslaved African Americans. Although the unknown road ahead still meant another 160-year human rights struggle for African Americans, our ancestors on June 19, 1865, still yelled in unison, “We Are Free.”

Thank you to Jerolyn Barbee, Assistant Director, and Derek Pridemore, Curatorial Intern at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, for this week’s post!

Established in 1988 in Wilberforce, Ohio, the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center (NAAMCC) shares the history, art, and culture of the African American experience and serves as a gathering place for the community. The museum is part of the Ohio History Connection’s historic site network. For more information about programs and events, visit ohiohistory.org/naamcc.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.