“Against the Moral Sentiment of Humanity”: The Fugitive Slave Act

In 1850, U.S. Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky introduced a series of five resolutions which, together, would become the Compromise of 1850. These decreed that Congress could not interfere with interstate slave trade, allowed Utah and New Mexico residents to vote on the status of slavery, admitted California to the Union as a free state, and abolished slavery in Washington, D.C. The fifth resolution included in the Compromise was the Fugitive Slave Act, which was enacted on September 18, 1850.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed Southern slave hunters to seize alleged runaways without due process and without proof that the individual was, in fact, an escaped slave. In fact, the captured person’s status as a free individual or fugitive slave was determined based on the testimony of the slave owner or slave catcher; the testimony of the captured individual had no bearing on whether he or she was taken into custody and enslaved in the South. According to Ohio Senate member Moses B. Walker, “The only question he is allowed to make, is as to his identity, and even this, as we have already seen in several cases, gives him but little chance for his liberty.” The law also forcibly compelled all Northerners to aid in the capture and return of escaped slaves, and imposed a $1,000 fine against any Federal agent who did not actively assist in enforcing the law. Similarly, any individual who obstructed the capture of fugitive slaves was also fined $1,000 and faced six months in jail. Northerners felt strongly that the law favored Southern plantation owners and infringed upon their rights, leading to increased regional tensions and strong resistance.

Ohio’s opposition to slavery has long been known and is well-documented by the collections in Ohio Memory. In last week’s blog post we featured the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, an event that was attributed in part to the legislation included in the Fugitive Slave Act. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (an excerpt of which can be viewed here) was one of the most powerful pieces of anti-slavery rhetoric ever published and was also a response to the Act. In fact, a visit with John Rankin, a strong abolitionist whose Ripley, Ohio, home was a stop on the Underground Railroad, provided some of the inspiration for the novel.

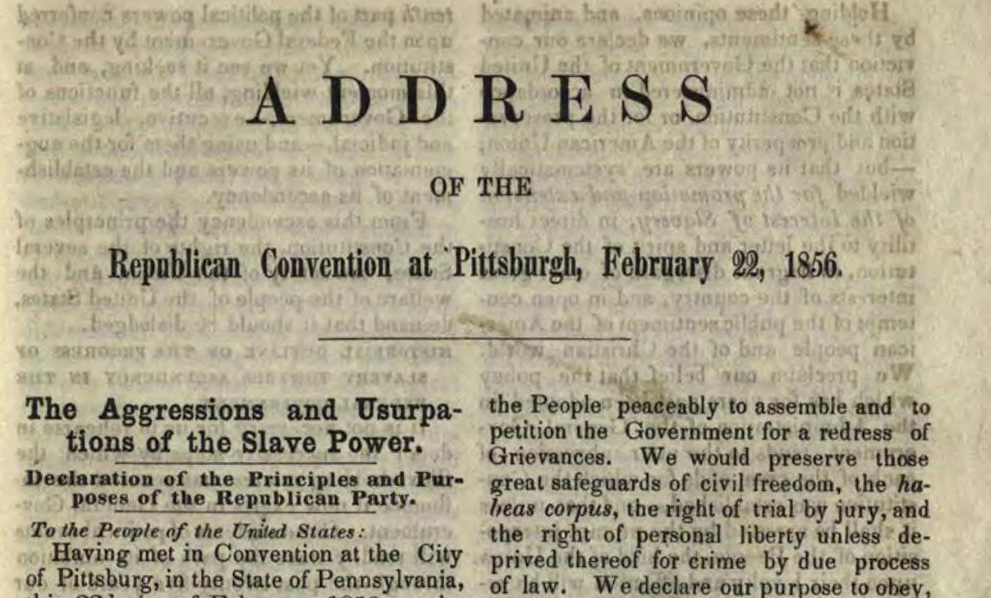

There can be no doubt that the Fugitive Slave Law and the resulting increase in tensions between the North and the South played a significant role in the buildup to the Civil War. Certainly, existing documents, including this pamphlet from the Republican National Convention in 1856, indicate high resentment in the North over the apparent preferential treatment of slave owners: “There is not a State in the Union in which the Slave-holders number one-tenth part of the free white population – nor in the aggregate do they number one-fiftieth of part of the white population of the United States…yet we see it seeking, and at this moment wielding, all the functions of the Government…and using them for the augmentation of its powers and the establishment of its ascendency.”

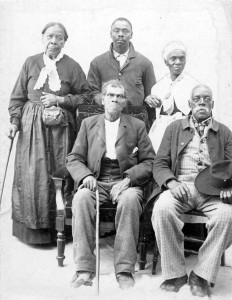

Despite the law, which remained in place until July 5, 1864, and despite the possibility of capture, slaves continued to utilize the avenues available to them in order to obtain their freedom. And despite the danger of being prosecuted, individuals acting as part of the Underground Railroad or on their own aided these individuals to the safety of the North. Though many are now lost to history, we are still able to see them in collections such as those in Ohio Memory. Think of them today.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital/Tangible Media Cataloger at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.