“Never Dubl a Leter”: The Phonetic Reform Movement

Ohio Memory has content related to many reform movements throughout history–abolition, women’s suffrage, temperance, prohibition and more. But one we don’t hear much about these days is the phonetic reform movement, sometimes called the spelling reform movement, championed in the 19th and early 20th centuries by such figures as Noah Webster (of dictionary fame). Melvil Dewey (known for his Dewey Decimal Classification), Mark Twain, President Theodore Roosevelt, and industrialist Andrew Carnegie.

Efforts to reform the spelling of the English language have been around for centuries, and continue even to this day. Emphasizing the “alphabetic principle” that says letters and their combinations should “represent the speech sounds of a language based on systematic and predictable [emphasis added] relationships between written letters, symbols, and spoken words,” phonetic reformers want the written form of English to be more consistent and more closely match pronunciation of the written words. The outcomes, they say, would be improved literacy, less wasted time and resources, and a language that’s easier to acquire and use for communication around the world. Calls for reform have varied from a desire to simplify spelling conventions, but still use our English alphabet, to an insistence on new letters and symbols to achieve consistency and predictability.

Two items in Ohio Memory document the spelling reform movement of the mid- to late-19th century, both available courtesy of the Geneva Library Branch of the Ashtabula County District Library. From the collection of Leander Lyon, a druggist in Conneaut, Ohio, who supported spelling reform, you can explore excerpts from the periodical Fonetic Techer, as well as a selection from Ferst Amerikan Reder, published in Cincinnati in 1863.

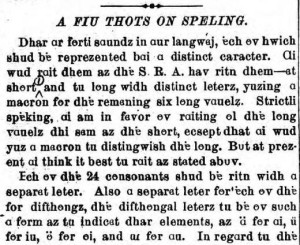

The Techer,intended to circulate among supporters of phonetic reform, includes correspondence and advertisements, as well as reports on progress of spelling reform, biblical translations, and even somewhat heated discussions of how to correctly represent words in a phonetic manner. Upon first glance at the volume, with its accent marks and variations on familiar English characters, it can seem like a foreign language. But the publication is an interesting challenge to browse, and the phonetic patterns soon become clear.

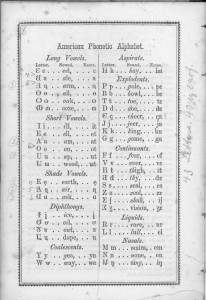

The Ferst Amerikan Reder, on the other hand, is meant to be used as a teaching primer for students learning phonetic spelling. It covers punctuation marks, the five senses, numbers and figures, and simple narratives illustrated by drawings. It also includes a chart of the American Phonetic Alphabet, as seen at left. The alphabet includes 43 letters, although Lyon has noted in the margins that “40 iz enuf.”

Interested in learning more after perusing these items on Ohio Memory? Elsewhere on the Internet, you can view digitized versions of the American Phonetic Dictionary of the English Language, Transactions of the American Philological Association (a leader in the phonetic reform movement), and the Fonetic Jurnal, beginning in 1851. Hapy reeding!

Thanks to Lily Birkhimer, Digital Projects Coordinator at the Ohio History Connection, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.