Writing History: The Tower of London

When we share materials via Ohio Memory, and when we discuss those materials in blog posts, we make every effort to be both accurate and impartial. In general, accuracy is the simpler goal of the two… so long as our sources are accurate, that is. Impartiality, however, is a bigger challenge. It can be very difficult to discuss a hot-button topic without letting our biases show. Today, we recognize this and work hard to put personal feelings aside, but this has not always been the case. Indeed, the sensationalizing of history was long the norm, with writers of historical non-fiction allowing their work to reflect personal feelings or a desire to make an event more exciting or interesting or to share select aspects of history for simplicity’s sake. This week’s featured items reflect this trend nicely.

The Tower of London is one of the oldest post-Norman conquest structures in England, with construction on the original section, the White Tower, having begun in 1078 under the rule of William the Conqueror. It was originally intended to be a royal residence and, in fact, housed multiple British monarchs, several of whom made additions or changes to the Tower until it became the structure we see today. Despite its original purpose, however, the Tower of London is best known as a prison and as the site of many executions dating back almost to its founding. Famous British monarchs, anarchists, religious figures, and others who angered or opposed the current ruler were sent there, sometimes for years.

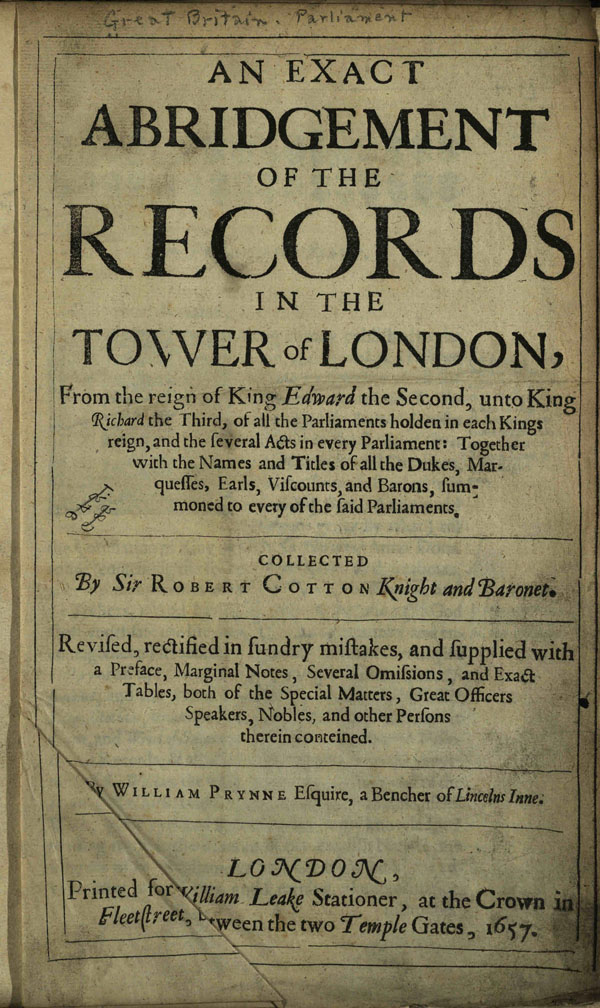

The State Library of Ohio holds two separate titles regarding the Tower of London in its Rare Books collection. The oldest of the two was published in 1657 and is an abridgement of the official Parliamentary records of the Tower. The historic records shared in the single volume span from 1307, the start of the reign of King Edward II, and end with the death of King Richard III in 1485. They were collected by Sir Robert Cotton of the famous Cottonian Library, one of the largest private libraries of manuscript materials ever collected, and were later abridged by William Prynne. The book is occasionally challenging to read, but Prynne provides a substantial preface with information on the book’s origins and organization. Prynne includes an index and footnotes in his publication, as well, increasing the impression of accuracy.

Prynne also answers those “supercilious persons” who “disdain” abridgements as being “not comparable” to full records by supporting abridgements as being smaller than full records, making them portable; as reflecting the “marrow, quintessence, and most remarkable useful material comprised in many large records;” as “omit[ting] and pare[ing] away superfluities;” as being less expensive, easier to remember, and easier to read; and as having been proven to be useful in other areas of study. He describes the value of abridgements as “one precious jewel or small piece of gold” as compared to “many pieces and pounds” of iron, brass, and tin. By the way, please note that the pagination in this volume is irregular, making some pages appear to be missing and others to be duplicated.

The second title relating to the Tower of London was published nearly 200 years later and is a history of the structure rather than a reprint of records relating to it. The two-volume History and Antiquities of the Tower of London (linked here and here) was published in 1821 by John Bayley and is drawn from the structure’s official records, though Bayley also notes that “other original and authentic sources” were consulted for the history, which covers the years from its foundation in 1078 to the 1800s. Bayley uses language to convey a sense of excitement and drama in his writing; for example, he describes the unpopular King Richard I as “thirsting for fame” and “burning with religious zeal,” while calling Queen Elizabeth I a “glorious heroine” and says that “never did the accession of a sovereign excite more sincere or general rejoicings than that of Elizabeth.”

Remarkably, when discussing the events surrounding the coronation of King Richard III, who is believed to have ordered his nephews murdered so he could take the throne, Bayley is even-handed in the description and evaluation of his sources, finally concluding that the sources are likely unreliable and that “implicit belief of his guilt so generally entertained by the world does not appear to be justified by the indecisive and prejudiced evidence whereon this judgment has been founded.” This is not to say that Bayley’s piece isn’t worth studying. In fact, it is an excellent source of information on the Tower of London’s history as a building and as a prison and the site of many executions over the years. That, in the second volume, Bayley describes many of the executions in a gruesome fashion doesn’t detract from the cases and, for some, might make history more readable. As with the first title on the Tower of London, pagination is irregular in this set.

Whether you take a “just the facts, ma’am” approach to history or prefer it with embellishments and sensational language, Ohio Memory has materials to suit your taste. Have fun exploring!

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.