The Captivity Narrative of John McCullough

Captivity narratives, especially those related to Europeans and Americans captured by American Indians, have been popular in this country since the 17th century, and the veracity of some of these stories is often debated. Captivity narratives traditionally have the captive recording their experiences in a storytelling format which typically features a protagonist, the “captive,” who is being held against his or her will. Most narratives tell the story of adult captives, but John McCullough, who was eight years old when he was captured, has provided us with a glimpse of the experience of a captive told from a child’s point of view.

McCullough was born in Newcastle, Delaware, in 1748, and his brother, James, was born in 1751. Their father moved the family multiple times between 1753 and 1756. When McCullough was eight years old and his brother was five years old, they were captured by members of the Delaware Nation. In the early days of their captivity, James was given away to a Frenchman, never again to be seen by his brother. In the meantime, McCullough spent what would amount to eight years with the Delaware. His father’s neighbor, John Martin, would eventually secure his release in 1756, at which point he returned to his parents. He wrote the narrative of his captivity fifty years later in 1806.

A copy of this journal lies with the State Library of Ohio. The narrative begins with McCullough’s birth before briefly covering a series of moves from one place to another by the family. Then, it proceeds to detail the circumstances that led to his capture. Throughout most of the journal, McCullough provides the reader with mundane details: playing with friends, moving, when the Delaware worked in the cornfields. However, some tales stuck out.

One instance involved a conflict between McCullough and another boy who had a gun. McCullough ran away out of fear after trying to persuade the other to lay down his gun. McCullough succeeded in convincing the boy to cease threatening him with the gun, but the boy was unable put the cock down and required McCullough’s help. He agreed only if the boy would point the butt towards him. Thus, the muzzle was facing the boy. Then, McCullough accidentally pulled the trigger, shooting him and leaving him dead. His testimony claimed that the boy had pointed the gun towards himself and pulled the trigger. When witnesses began to appear, claiming that McCullough was the one who had actually shot the boy, he maintained his innocence. Eventually, a woman who he knew had seen the entire fiasco with the gun spoke up, asserting McCullough’s innocence. The matter was put to rest after this.

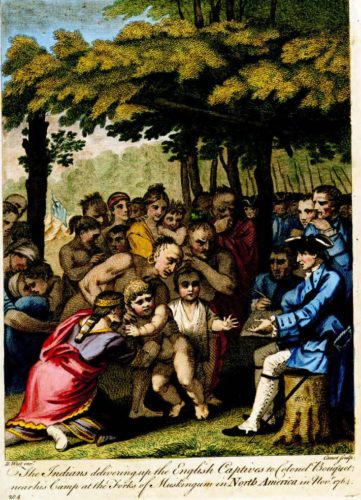

McCullough continued to stay with the Delaware tribe. He became assimilated to their lifestyle, learning to speak the language (and losing English) and becoming a member of a Delaware family, with whom relations seemed amicable. In 1762, John Martin, looking for his own family, arrived at a prisoner camp at which McCullough was living. He freed them, as well as McCullough. McCullough went to his father’s new home, not much further from the old one, and recounted the many times when Providence had saved him. He concluded the narrative by saying that some details from his years in captivity were omitted for fear that people would call them lies.

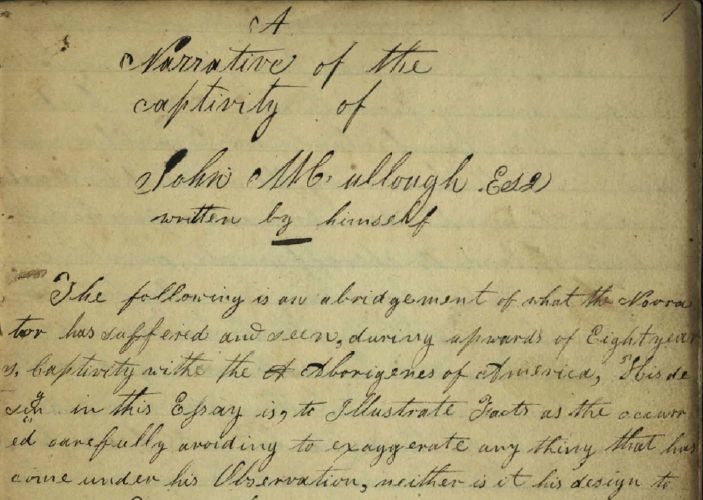

While the narrative clearly states it concerns the captivity of John McCullough, confusion may arise when one views the first page of the copy held by the State Library of Ohio. Upon doing this, the reader can ascertain that two different McCulloughs are represented: John McCullough, the author of the captivity narrative, and David McCullough, who inscribed this copy of the manuscript in 1834, more than a decade after John McCullough’s death in 1823. When skimming through the journal, it is evident that there are at least three different forms of handwriting used to record the events of McCullough’s life. While it is possible that John McCullough wrote some of the account and dictated the rest or perhaps simply dictated the whole narrative, it is highly unlikely given the inscription and notes on the front page and the date of his death.

That being said, we hoped to confirm to whom the writing samples belonged, and during our research we located an original manuscript of the narrative in the Pennsylvania Archives. Many thanks go to Archivist Aaron McWilliams, who quickly provided us with samples of the McCullough manuscript in their collection. Unfortunately, these clues did not result in a conclusion as to the writers of our manuscript, but based on the inscription in our manuscript and on the sample we received from Pennsylvania, we are confident that John McCullough did not write in our copy. Also, another feature of the writing on the pages that modern readers will find unusual is that it is crammed in onto each page as best as possible. For instance, floating letters of incomplete words at the end of a line are not hyphenated; rather, they just continue onto the next line, making discernment a challenge.

Recognizing that this writing may be challenging for modern readers, we have located a published copy of McCullough’s text here (please note that this link will take you to Google Books and is unaffiliated with Ohio Memory or any of its partners). Whichever way you access it, however, I would highly recommend viewing the manuscript copy on Ohio Memory.

Thank you to Desmond Bolden for this week’s post! Desmond is a senior History major at Kent State University with a planned graduation date of December 2018. He plans to pursue a Master’s degree in Library Science and is working at the State Library of Ohio to learn more about the process of becoming a librarian.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.