The Library War Service in Ohio

Earlier this month, we shared the history of Camp Sherman on the Ohio Memory blog. This week, we would like to revisit Camp Sherman, focusing specifically on one aspect of soldiers’ experiences there: the Camp Sherman library, as established by the Library War Service.

During World War I, Camp Sherman’s Major General Glenn wrote to W. H. Brett, a librarian at Cleveland Public Library, asking him to help change the perception that soldiers don’t have time to read, and to encourage donations for camp libraries. Glenn emphasized that “there is no one thing that will be of greater value to the men in his cantonment in producing contentment with their surroundings than properly selected reading material.”

Libraries across Ohio answered the call. In 1917, the American Library Association authorized the State Library Commissioners to take charge of Library War Service in Ohio. The board created the statewide book drive, called the Book-for-Every-Soldier campaign, which held book drives in every county. Over 250,000 books were donated to this campaign. The State Library of Ohio’s Traveling Library program also loaned 500 volumes to the 7th Regiment of the Ohio National Guard.

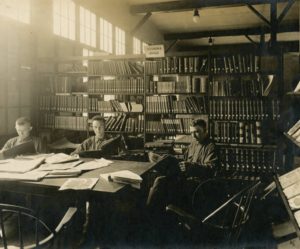

Many of the books gathered in Ohio were directed to the camp library at Camp Sherman, which was located near Chillicothe. A librarian from the Chillicothe Library, Burton Egbert Stevenson, was appointed as the Camp Librarian. Stevenson was a noted novelist and war activist. During the war he was a prolific writer in the War Library Bulletin and ALA War Service Library Report for Congress. At Camp Sherman, Stevenson worked to have a comfortable and well-stocked library of 40,000 volumes. To create an atmosphere of comfort and a sense of home, he successfully advocated for a fireplace in the library.

In addition to the book drives, Stevenson wrote to every newspaper published in Ohio and western Pennsylvania, requesting five complimentary copies of each publication for the library. His efforts resulted in over 300 papers delivered to the camp. Along with the fireplace, these newspapers gave soldiers a reminder of home with the local news coverage from their own hometowns.

In the ALA War Service Library Report, Stevenson noted that soldiers’ interest in books challenged his expectations. While the men often read fiction, he wrote, “when I started this work… I had some very plausible theories about the kinds of the books the men would want; but I soon discarded them. We have requests for every sort of book, from some books by Gene Stratton Porter to Boswell’s ‘Life of Johnson’ and Bergson’s ‘Creative Evolution.’ We have had requests for Ibsen’s plays, books on sewage disposal, and so many requests for ‘A Message to Garcia’ that I had a supply mimeographed” (1918). Only banned books – such as those advocating pacifism, or with pro-German, anti-capitalist, or pro-socialist themes, were not made available by Stevenson and other camp librarians like him. However, Stevenson continued to work to have a wide variety of books for the soldiers, and contributions from libraries and parlors across the state helped him achieve this goal.

The Library War Service hit its peak in 1919 but continued directing reading materials towards service members into the post-war period through 1920. Meanwhile, Camp Sherman was one of the last World War I Army training camps to be decommissioned in 1921. Additional information on camp libraries and the Library War Service’s efforts can be found via the following sources:

- The American Library Association Archives: A Book for Every Man: The ALA Library War Service

- The American Library Association: Library War Service

Thank you to Penelope Shumaker, Metadata Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.