John Wesley Powell and the American West

The United States Geological Survey was established in 1879 to classify public lands and study their geology and natural resources. The way it carried out this mission was largely shaped by its second director: an adventurer, scientist, and former Ohioan named John Wesley Powell.

Powell was born in Mount Morris, New York, in 1834, the son of an itinerant preacher. His family moved to Jackson, Ohio, when he was about four years old and lived there for eight years before moving to Wisconsin and eventually settling in Illinois.

Powell loved nature and the outdoors and had a penchant for wandering and exploring; in his early twenties, he took several river trips that included rowing sizeable sections of the Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois Rivers. He taught school while studying at Illinois, Wheaton, and Oberlin Colleges, but didn’t complete his degree. In 1860, he switched his focus to military science and engineering in order to prepare for the looming Civil War.

In May 1861, Powell enlisted as a private in the 10th Illinois Infantry, planning to work as a cartographer, topographer, and engineer. Later that year, he took a brief leave to marry Emma Dean. In 1862, Powell lost most of his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh. After recuperating and returning to the Army, he participated in the siege of Vicksburg, the Atlanta campaign (where he was promoted to major), and the Battle of Nashville.

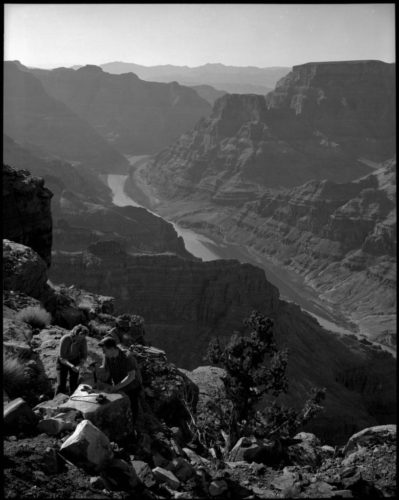

After the war, Powell accepted a position as a geology professor at Illinois Wesleyan University and served as curator of the museum of the Illinois State Natural History Society, but declined a permanent position in order to explore the American West. Starting in 1867, he led multiple expeditions to explore the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado River. In 1869, Powell and his team became the first people of European descent to travel the length of the Grand Canyon—a journey of three months and more than 900 miles. During the trip, the team (which originally numbered ten men) rode the river through smaller rapids and portaged their four boats and supplies around larger ones. However, the journey was a difficult one through unknown territory. The team lost two boats and the bulk of their supplies to the river, and had no way of knowing what lay ahead of them. One of the men left the expedition at a resupply stop after the first month. Several weeks later, at a place now called Separation Canyon, three additional members of the team decided the journey ahead was too dangerous; they climbed out of the canyon and started walking toward civilization. They were never seen again. Two days later, Powell and the remaining five team members reached the mouth of the Virgin River, where they were met by settlers.

The Grand Canyon expedition made Powell a national hero and led to speaking tours and a second expedition in 1871–you can see images of the 1871 expedition and photos of John Wesley Powell from the National Park Service here. In 1881, Powell was appointed the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, where he was in charge of exploring, mapping, and classifying the West.

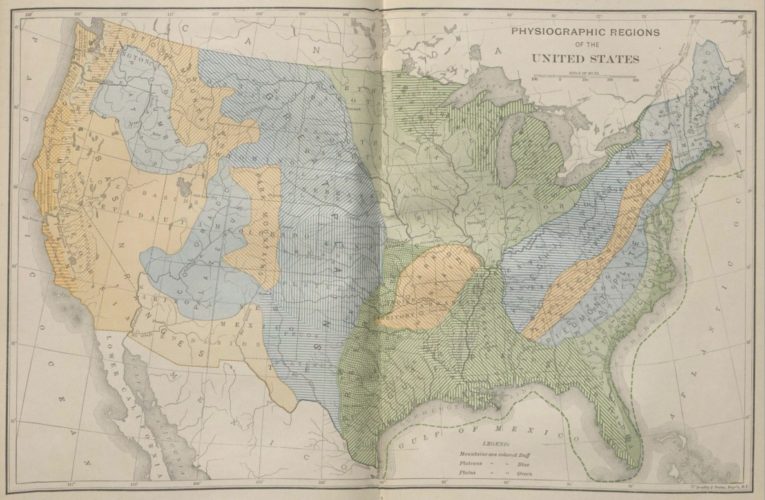

Powell believed that the vast majority of the West was too arid for agriculture; instead, he proposed conservation, low-density open grazing, and settlement and land use based on watershed areas and topography rather than arbitrary political boundaries. However, railroads and other business interests with large land holdings lobbied Congress in favor of widespread agricultural settlement in order to cash in on their land. Congress sided with the business interests and passed legislation that encouraged pioneer settlement. After his appropriations were cut, Powell resigned his post in 1894. His views on Western development would be vindicated decades later by the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

In addition to his work at the Geological Survey, Powell held two additional posts during the late 1800s. In 1888, he was one of 33 founding members of the National Geographic Society. He also served as the first director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology from its creation in 1879 until his death in 1902. Under Powell’s leadership the Bureau conducted ethnographic and linguistic field research about American Indian nations, produced a series of publications, and promoted the relatively new field of anthropology.

Powell died of a cerebral hemorrhage in September 1902. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in recognition of his service to the nation.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.