“Where Do We Go From Here?”: World War I Veterans at Home

November 11, 2018, marked the World War I Armistice Centennial, and Americans remembered the honorable men and women who served in the Great War. These types of anniversaries often inspire us to learn more about soldiers’ and sailors’ training regimens and daily life, as well as the harsh conditions they survived and the treacherous landscapes they traversed. But, another important aspect of World War I, or any armed conflict, is what happens to servicemen once they return home. After the parades and joyous welcomes from beloved family and friends, what resources were available to help the 4.7 million World War I veterans readjust to civilian life?

The history of government-funded veterans benefits dates back to 1776 when the Continental Congress established the United States’ first pension law, granting half pay to Revolutionary War veterans suffering from serious disabilities. After the ratification of the constitution in 1789, the federal government assumed responsibility for veterans’ pensions, which were previously disbursed by state governments. Federal officials revised U.S. pension laws several times over the following decades, including a need-based service pension for Revolutionary War veterans. The needs of almost 2 million Civil War veterans prompted more progressive laws and programs, including compensation for diseases incurred during service and a large-scale national effort to provide medical care for veterans.

Prior to America joining World War I, the Sherwood Act (1912) granted pensions to all veterans, regardless of disability, at age 62. Once the U.S. joined World War I, the unprecedented enormity of mobilized troops forced the federal government to ensure the well-being and financial stability of servicemen and their families. Originally passed in 1914 to insure American ships and their cargo, and later expanded to include men killed, captured, or injured while aboard merchant ships, the War Risk Insurance Act was amended in 1917 to offer three basic benefits: to support servicemen’s families through allotments and allowances; to compensate families in cases of death or disability; and to offer low-cost insurance coverage.

This act marks the first time the federal government offered family allowances to protect their finances while the main bread-winner was away. Servicemen paid insurance premiums out of their monthly pay, but could also pay a $15 monthly allotment so that the government would send monthly allowances of no more than $50 to their dependents, with the allowance amount based on family size. In case of injury or disability, the government provided monthly compensation for men and their families.

Soldiers and sailors received $60 upon honorable discharge, and were then responsible for maintaining their insurance coverage by continuing to pay their monthly premiums. Five years after honorable discharge, servicemen could decide whether they wanted to continue their coverage or start a policy with a private insurance company or employer. However, private companies often would not sign on men with serious war-related health conditions and charged more expensive premiums.

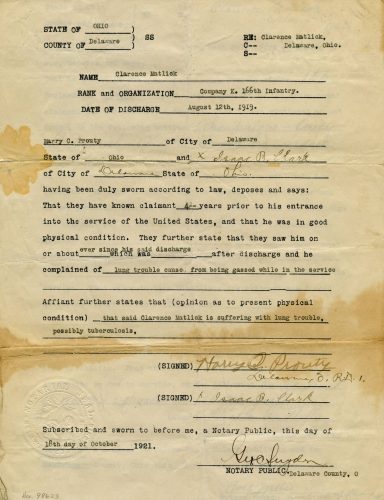

Although the provisions within the War Risk Insurance Act protected soldiers’ families during the war, veterans returned with physical and emotional scars, many of them permanently disabled and unable to work. The government paid for medical, occupational, and rehabilitative care for injured and disabled veterans, as well as monthly compensation. Veterans could enroll in government funded vocational training through the Federal Board of Vocational Education, and receive a training stipend of $65 per month or more.

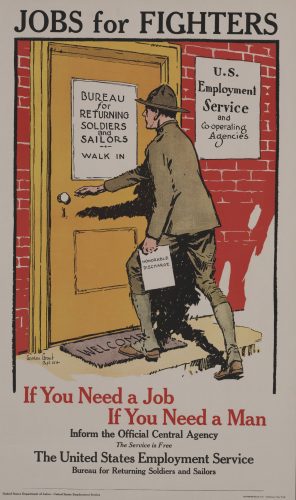

Many organizations like the Red Cross, American Legion, Disabled American Veterans, and the War Camp Community Service distributed literature detailing how to receive proper medical and rehabilitative care, collect due compensation, find jobs, and handle financial situations that occurred while they were away, like lapsed mortgages and pre-war insurance policies. These organizations, particularly the newly-formed American Legion, fought for veterans’ rights and pushed for increased educational benefits to help disabled veterans learn new marketable skills so they could work.

Although partially-disabled veterans received compensation through the War Risk Insurance Act, many veterans suffered financially because monthly disability compensation was often not enough to make up for the individual’s loss in earning power, as he could not return to work making his pre-war income. In 1917, the Red Cross opened the Institute for Crippled and Disabled men in New York to train amputees and individuals with decreased mobility, and by the war’s end most of its patients were veterans. The War Camp Community Service worked with companies to hire veterans and those whose war work jobs were now terminated. Many companies hired back previous employees once they returned from the service, and tried to open other positions to keep workers who had temporarily replaced servicemen.

Despite these combined efforts, veterans often did not receive the care and assistance they needed to reintegrate into society and gain financial stability for their families. Unfortunately, unemployment and poor housing conditions were realities for many veterans, not to mention the blatantly unwelcome reception of returning African American soldiers, leading to the 1919 race riots and the eventual Bonus March in 1932.

Although far from a success, one might consider the World War I era to be the United States’ first concerted effort to care for veterans and meet their needs. Although the government failed these men in many ways, we continue to remember them by sharing their stories and honoring their memories.

Thanks to Kristen Newby, project coordinator at the Ohio History Connection, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.