Stop the Presses! Antique Typography

Today we’re sharing an item from the State Library of Ohio’s Rare Books collection: a typography specimen book from 1859!

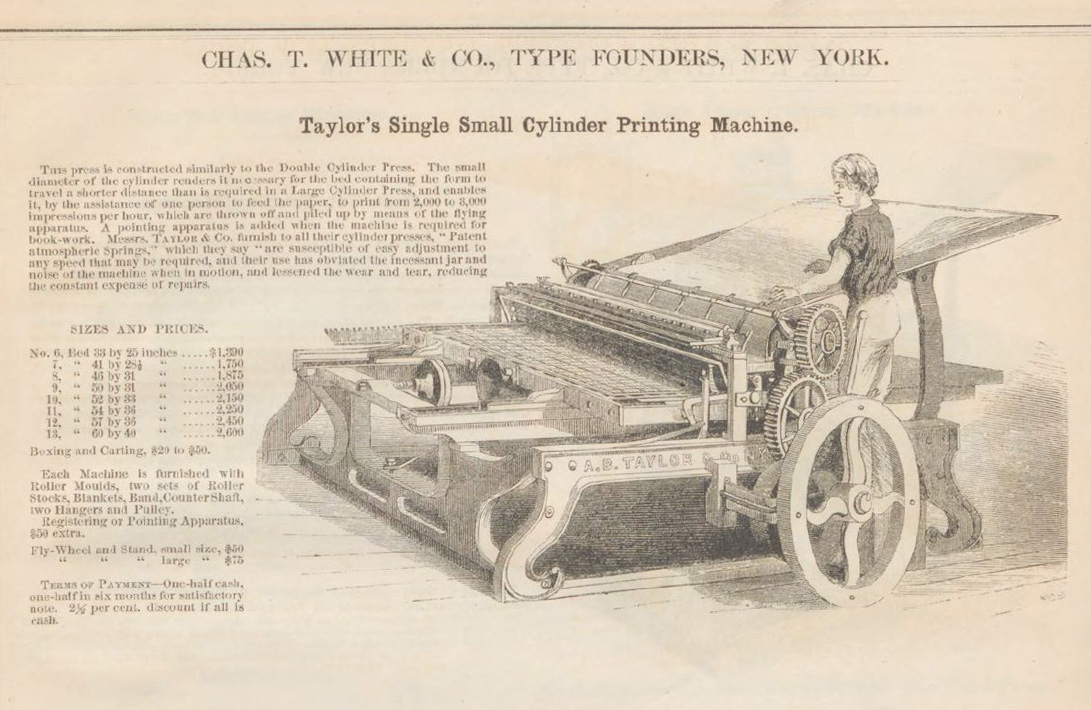

In the mid-1800s, the printing process was surprisingly similar to the process developed by Johannes Gutenberg 400 years earlier. Individual metal or wooden letters, formed in reverse, were arranged inside a frame and covered with a thin layer of ink. The press was then used to push paper against the letters, creating a print. Steam-powered iron presses had replaced Gutenberg’s human-powered wooden design in the early 1800s, and rotary presses (which fed large rolls of paper into the press instead of single sheets) had been introduced in the 1840s, but the process of arranging text by hand, letter by letter, remained largely unchanged. The metal letters and decorative elements used in this process were created by type foundries.

Two relatively large foundries were located in Ohio—the Cincinnati Type Foundry (established in 1817) and the Cleveland Type Foundry (established in 1875). Both sold printing presses in addition to designing typefaces and manufacturing the metal type pieces used in printing. The Cincinnati Type Foundry even manufactured small, portable printing presses for the Union Army beginning in 1862. Production was stopped after the war, but soon resumed due to popular demand. You can see a post-war version of the press from the Smithsonian’s collection here.

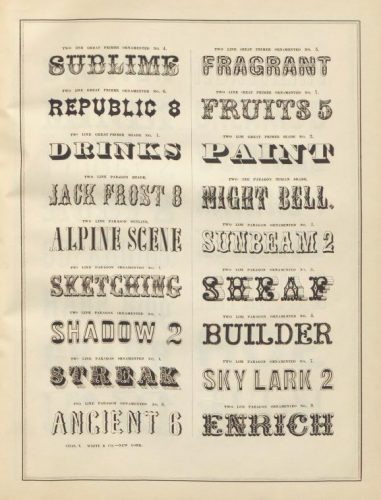

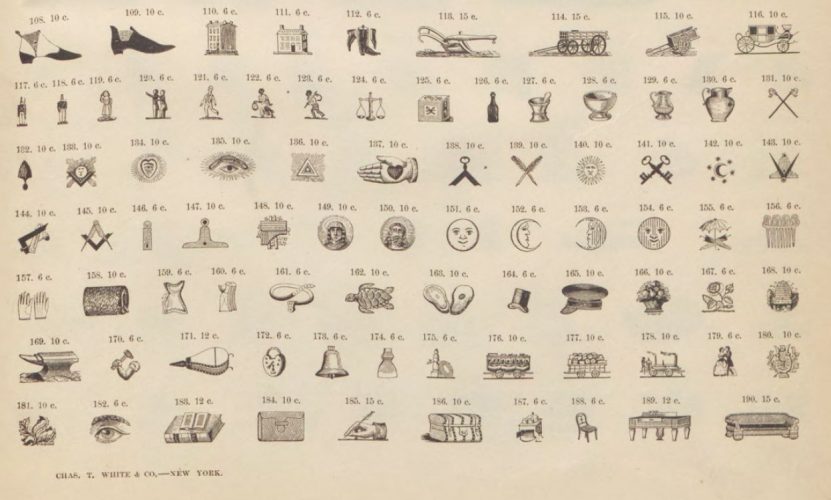

This 1859 specimen book from the State Library’s collection is an abridged version of the Chas. T. White & Co. 1858 catalog, designed to be mailed to out-of-state customers. Although this book isn’t from an Ohio foundry, it’s an excellent example of the work produced by type foundries in the 1800s. In addition to typefaces, the foundries also created decorative rules, borders, and ornaments to be used as design elements in printing projects. Many digital fonts used today are based on typefaces originally developed by nineteenth-century foundries.

In the 1880s, the invention of the linotype machine, which allowed an operator using a keyboard to create an entire line of text at once instead of hand-setting the text letter by letter, revolutionized the printing industry. In 1892, 23 U.S. type foundries representing 85% of the domestic type manufacturing market, including the Cincinnati and Cleveland Type Foundries, merged to form the American Type Founders company. By eliminating duplication and focusing on larger display and advertising type instead of smaller body type (where the linotype machine excelled), the company flourished until the Great Depression, from which it never fully recovered.

Note: What’s the difference between a typeface and a font? A typeface is a set of glyphs (letters, numbers, punctuation) with a common design—for example, Times New Roman. A font is a subset of glyphs within a typeface; Times New Roman Bold and Times New Roman Italic are different fonts. Today the terms are used interchangeably.

Today, despite the widespread use of digital publishing and printing, letterpress printing is making a comeback. And although some modern letterpress printers use photopolymer or 3D-printed type pieces, others still use salvaged pieces from the nineteenth-century foundries.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.