Happy Birthday to Edgar, to Gustav, and to the Raven!

Masters of literature know exactly how to set a tone from the very first line of a piece. With “Once upon a midnight dreary,” Poe created the perfect gothic atmosphere: it’s late at night, dark and, likely, quiet, exactly the time in which one is tired and when one’s imagination is likely to drift to frightening places. Meanwhile, great artists know how to turn ideas into objects that elicit an emotional response – joy, fear, sadness – from the viewer. The 1884 imprint of The Raven, written by Edgar Allan Poe and illustrated by Gustav Doré, is a gorgeous example of how great masters create gorgeous works.

January brings four notable dates related to our imprint of The Raven, the first two being from the Poe-verse: the birthday of the author on January 19th, and the publication anniversary of the poem, one of his most well-known works, on January 29th. What’s more, the artist who beautifully illustrated Poe’s Raven, Gustav Doré, was born on January 6th and died on January 23rd. Though we presented The Raven to our blog readers in October 2014, we would like to celebrate these dates by delving a bit more deeply into it and, hopefully, introducing new readers to the lovely imprint that’s available for viewing in Ohio Memory.

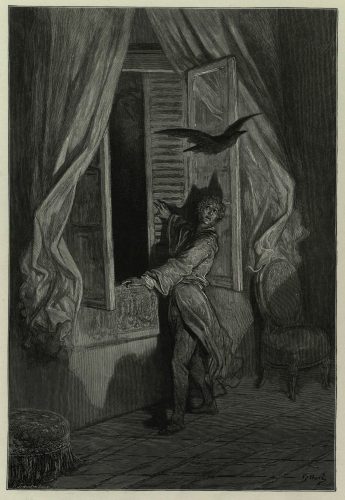

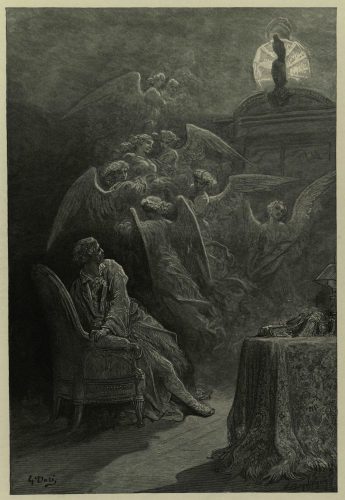

When Poe wrote and published The Raven in 1845, he was already a writer of renown, having released his first collection of poetry, Tamerlane and Other Poems, in 1827. Despite nearly twenty years of steady work, however, it was the story of the increasingly-mad narrator and his bird companion that made him a household name. In The Raven, a young man sits alone, late in the evening, mourning the loss of his beloved, Lenore, when a raven taps on his window. The young man lets the raven in and asks the bird its name. The only response, of course, is “nevermore,” and it is this one word, spoken over and over to an increasingly-upset audience, that leads the young man to madness.

Poe was, unfortunately, well-acquainted with grief, and that likely enhanced his ability to depict it in his writing. His mother, foster mother, and brother all died of tuberculosis and, after a falling-out, his foster father, whom Poe admired greatly, cut him off completely. While he was writing The Raven, his wife was ill, also with tuberculosis and, having seen its effects, Poe recognized that her death was imminent. Mental illness and alcoholism have been suggested as having contributed to Poe’s genius in the gothic genre (more on that in a moment), but it’s more likely that Poe was, to put it simply, just sad.

As to mental illness and alcoholism: after Poe’s death in 1849, the first obituary written about him was authored by a rival, Rufus Griswold, who appears to have made up disparaging stories about the author to destroy his reputation. According to the Edgar Allan Poe Society, Griswold saw Poe as morally and intellectually inferior. Meanwhile, Poe believed Griswold to be lacking in talent, his success due more to his fortunate birth than his writing ability. When Poe died, Griswold apparently seized upon the opportunity to discredit Poe, first with the obituary and, later, with a biography. In truth, though it has been long said that Poe drank himself to death, there is no evidence of that being the case outside of Griswold’s claims (see The Poe Museum).

Less information about the life of Gustav Doré is readily available. Like Poe, he was a master of his medium, but he was certainly more successful; though Poe never saw financial success for his work, Doré achieved great fame and financial success during his lifetime. His medium was most typically woodcuts (our previous blog post about this volume of The Raven stated that the illustrations were steel engravings, which was incorrect), but he also sculpted and painted, though to less critical acclaim. He was a prolific illustrator, creating art for imprints of Don Quixote, Rime of the Ancient Mariner (which is also available on Ohio Memory), Paradise Lost, and the Bible (the State Library of Ohio, an Ohio Memory partner, holds a copy of the Doré-illustrated Bible in its special collections, viewable on request when the library reopens to the public). Doré received payment for his work on The Raven in 1883 but died before its publication in 1884.

For more information on Edgar Allan Poe, The Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, is an excellent resource. The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore’s website is a rich resource on Poe and includes links to his various works, his letters, biographies about Poe, and other collected works. The works of Gustav Doré can be seen on WikiArt. With the exception of the links to The Raven and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, all links resolve to external sites.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer-Trausch, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.