Exploring Old Photographs: Real Photo Postcards

This week we’re wrapping up our series about old photographs on paper by featuring real photo postcards (also called RPPCs) and the rise of amateur photography.

In 1900, Eastman Kodak introduced the Brownie, a camera that took photography out of studios and into everyday life. Originally marketed to children, its small size and $1 cost (roughly $35 in 2022 dollars) made amateur photography available to the masses. Three years later, Kodak introduced the No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak. It was specifically designed for postcard-sized film that created postcard-sized negatives, allowing amateur photographers to take photos and have them developed onto preprinted postcard backs.

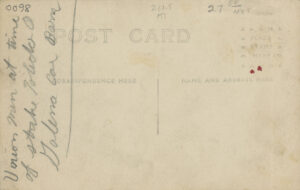

In 1907, Kodak introduced “real photo postcards,” a service that enabled customers to make a postcard from any photo they took and send it through the mail. It’s important to note the difference between real photo postcards and standard postcards, which were created with lithographic or offset printing. With strong enough magnification you can see that printed postcard images, much like pictures in a newspaper, are created with dots. RPPCs, on the other hand, are continuous tone, actual photographs developed from a negative onto photographic paper with postcard backs.

Up to this point, postcards had no dedicated space for messages; the postcard back was reserved for the address, so the sender had to write any notes to the recipient on the front of the card. An act of Congress on March 1, 1907, finally divided the back of the postcard to allow space for a message as well as the address, and the popularity of RPPCs exploded. Ordinary people could now use photographs to document and share images of everyday life: families and neighbors during leisure time, city and village streets, work on factory floors and family farms, and more.

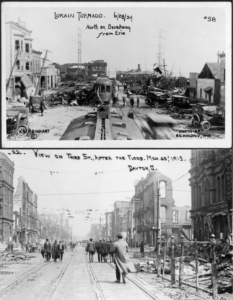

Although some professional photographers treated “postals” as a fad, the public embraced them. Photography studios that focused on RPPCs often flourished in smaller towns that might not have a regular studio. Portraits were generally the most popular subject, but local buildings and attractions such as sports teams, county fairs, and even local disasters were also popular. Images of national events, including social and political movements, had an even wider audience.

Professional printing companies also created and sold mass-produced RPPCs; a negative was loaded into a machine that repeatedly exposed the image on a roll of photographic paper. Some RPPCs were hand-tinted or included three-dimensional embellishments, such as ribbon or glass eyes.

The heyday of real photo postcards stretched from just after the turn of the century until the invention of CMYK color printing in the 1930s. However, real photo postcard production continued until the middle of the twentieth century. Below are some tips for dating real photo postcards:

• A cancellation stamp is the easiest way to date a postcard.

• The stamp box on the back of a real photo postcard can also help date the card, assuming the box is visible. (An online search for “How to Identify and Date Real Photo Vintage Postcards” will lead to a website featuring date ranges for various stamp box designs.) For example, the stamp box on the back of the striking workers postcard in this blog post shows the word Azo (a photographic paper manufactured by Eastman Kodak) with four upward-pointing triangles in the corners; this design was used from 1904-1918. Because the postcard has a divided back, we can narrow the date range a bit more to 1907-1918.

• Early RPPCs used thinner cardstock and had matte backs. Later cards used thicker stock.

• As with cartes de visite and cabinet cards, hairstyles (including men’s facial hair) and clothing can help date the image. For photos taken outside, environmental clues (such as types of transportation) can also help.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at the State Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.