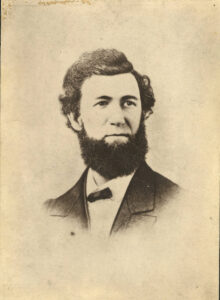

Benjamin Hanby: A Life in Music

Although he may not be a household name today, Ohio native and songwriter Benjamin Hanby was famous in his time—his first professionally published song reached the nineteenth-century equivalent of multi-platinum status. However, Hanby didn’t seek fame or fortune; he truly tried to make the world a better place.

Benjamin Hanby was born near Rushville, Ohio, on July 22, 1833. His love of music started at an early age; he had a paper route as a boy (delivered via horseback) and used his earnings to buy his first musical instrument—a flute—when he was fourteen.

Benjamin’s father, William Hanby, had been an indentured servant as a young man and strongly opposed fugitive slave laws. In 1847, William was one of the founders of Otterbein University in Westerville, Ohio. Otterbein was one of the first universities in the country to welcome women and people of color, and was also one of the few institutions where women took the same classes as their male counterparts. City and university officials supported emancipation, and Westerville became a significant stop on the Underground Railroad.

In 1849, Benjamin moved to Westerville and enrolled at Otterbein. In addition to editing the student newspaper, he ran an infant school (similar to today’s kindergarten) to help pay for tuition and expenses. To save money, he and a friend lived in an old cabin off campus. Benjamin built some of the furniture, including a desk that sits in the Hanby House today. Because he had to work for tuition money during his time at Otterbein, it took him nearly nine years to graduate. He had no formal musical training, but regularly traveled three miles each way to practice on the nearest piano.

William Hanby moved the rest of his family to Westerville in 1853. He had previously worked with the Underground Railroad in Rushville, and worked with Otterbein’s president, Lewis Davis, at the Westerville station. Hanby and Davis were neighbors, and their wives would help feed and shelter the Railroad’s passengers. Late at night, Benjamin would walk the streets to make sure it was safe to move the passengers on to the next station.

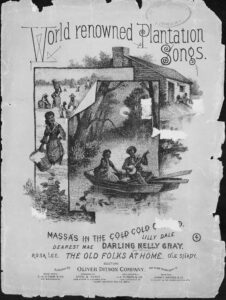

William bought a piano for the new house, making it much easier for Benjamin to practice. In 1856, Benjamin’s music teacher encouraged him to submit a song that he had written and composed, titled “Darling Nelly Gray,” to a publisher. The song was based on Joseph Selby, an escaping enslaved man who found shelter at the Hanby’s Rushville home in 1842. Selby was trying to reach Canada and earn enough money to purchase freedom for his fiancée, but he died at the Hanby’s home and was buried in the Rushville cemetery. “Darling Nelly Gray” was a huge success; it captured listeners’ hearts in the same way Uncle Tom’s Cabin had captured the hearts of readers.

Benjamin married his college sweetheart the day after his graduation from Otterbein in 1858. He held several jobs over the next few years, including teacher, school principal, and minister, and he also opened a singing school. Through it all, he continued to write music.

In 1865, George Frederick Root published Hanby’s song “Up on the Housetop” (thought to be the second-oldest secular Christmas song after “Jingle Bells”) and brought Benjamin and his family to Chicago. Benjamin organized children’s concerts and singing schools throughout the Midwest, co-authored a quarterly musical publication for children, and continued to compose new songs and hymns.

Benjamin Hanby produced more than eighty songs in his lifetime. He died of tuberculosis in 1867, aged 33, and is buried in Otterbein Cemetery in Westerville.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at the State Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.