“American Notes for General Circulation”

This holiday season, you may have read or watched a version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Published in 1843, A Christmas Carol is perhaps Dickens’ most beloved novel and is a tradition for families worldwide.

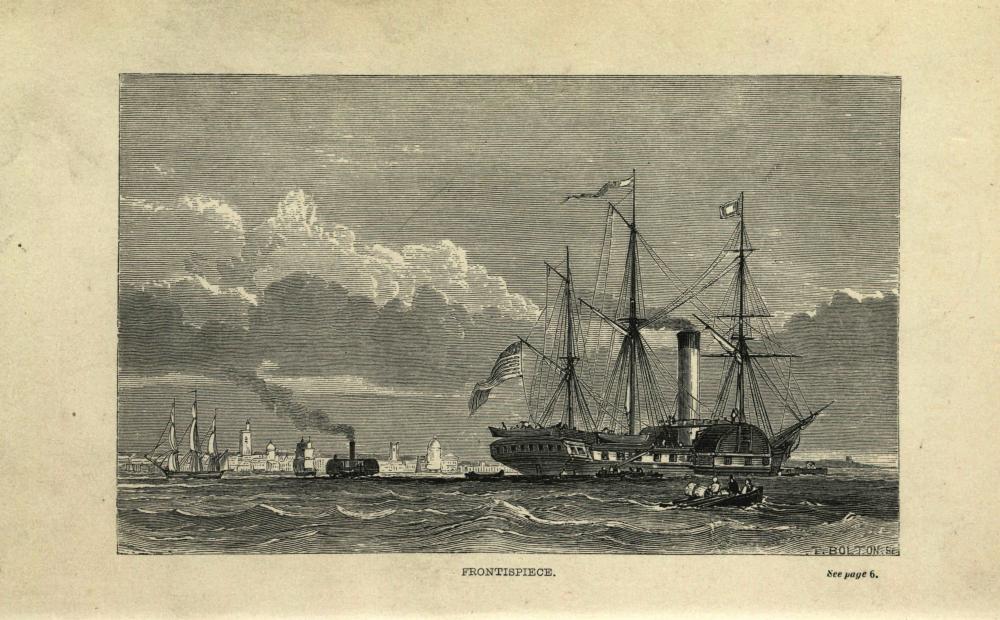

A year before A Christmas Carol was published, Dickens traveled to the United States for an extended visit. The resulting travelogue, published that same year, received a far different reception than Dickens’ other works. The travelogue was entitled American Notes for General Circulation (generally just called American Notes), and it enraged Americans with the apparently condescending and mocking tone that was directed toward the people Dickens met and the places he visited during his travels.

Dickens’ works focused on social inequity and, particularly, on the poor treatment of those who were on the lower levels of the socioeconomic ladder. He had a keen eye for injustice and used satire to shine a light on the absurdities and cruelties of human nature. Dickens’ writing was funny but, as is the case with satire, whether one found it funny depended upon one’s personal views. Still, most readers today will enjoy the following exchange he witnessed while waiting for a stagecoach headed for Columbus, in which Dickens identifies the speakers based on the hat they are wearing:

Brown Hat: This coach is rather behind its time to-day, I guess.

Straw Hat (doubtingly): Yes, sir.

Brown Hat (looking at his watch): Yes sir; nigh upon two hours.

Straw Hat (raising his eyebrows in very great surprise): Yes, sir!

Brown Hat (Decisively, as he puts up his watch): Yes, sir.

All the other inside passengers (among themselves): Yes, sir.

If this conversation were to happen today, it would be appropriate to replace “yes, sir” with “dude.” See? Funny!

He also discusses the interchangeable coachmen he met along the way, saying there is “no change or variety in the coachmen’s character… He always chews and always spits, and never encumbers himself with a pocket-handkerchief. The consequences to the box passengers, especially when the wind blows towards him, are not agreeable.”

Incidentally, during his Ohio visit Dickens spent time at the Golden Lamb Inn – then called the Bradley House – in Lebanon. According to Historic Lebanon Ohio, Dickens was less than generous when describing his time there, complaining that, because the Golden Lamb was a temperance hotel, he was denied brandy. He was then offered either tea or coffee, and proclaimed that both were bad and that the water was worse. He went on to say that “This preposterous forcing of unpleasant drinks down the reluctant throats of travelers is not at all uncommon in America.”

In his conclusion, Dickens describes Americans, in general, as “by nature, frank, brave, cordial, hospitable, and affectionate.” What follows, however, is less than complimentary. He says that Americans elect officials that they do not trust, then take pride in the fact that they have the good sense to not trust the very people they have elected to office. He also points out that the American people have a “love of ‘smart,’” in which “smart outweighs all evils”: “He is a public nuisance, is he not?” “Yes, sir.” “A convicted liar?” “Yes, sir.” “He has been kicked, and cuffed, and caned?” “Yes, sir.” “And he is utterly dishonourable, debased, and profligate?” “Yes, sir.” “In the name of wonder, then, what is his merit?” “Well, sir, he is a smart man.”

He calls the Press “licentious,” and says that he cannot agree with other writers who suggest a lack of established church would decrease the prevalence of dissent in American because the “temper of the people” is such that they wouldn’t go, anyway. He devotes an entire chapter to slavery, expressing his disgust with the institution at every turn. Dickens certainly did not shy away from controversy!

Dickens knew that his words would anger the Americans who read them, and said as much in his final paragraphs. He also expressed hope that, in time, he would be forgiven. By the time of his second visit to America from 1867 to 1868, any anger that had been directed his way was long forgotten and he was, again, adored by the American public… as he remains to this day.

We hope you enjoy reading Dickens’ American Notes, and that you’ll take time to discover the other unexpected treasures to be found in Ohio Memory!

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital/Tangible Media Cataloger at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.