Worth a Thousand Words

Imagine life without photographs. There would be no way to quickly and easily capture images of friends and family, no in-the-moment snapshots of vacations, no selfies. Social media – Facebook, Pinterest, Twitter – would be radically different, as would most online sources of information. There would be no yearbooks and no photo albums. Really, the list is endless. Photographs are completely integrated into our daily lives and have altered the cultural landscape (see “selfie,” above, which is a case-in-point).

176 years ago, François Arago announced the daguerreotype process at a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des beaux arts. The process, developed by Louis Daguerre and a number of partners, utilized a chemical reaction and exposure to light to render images on a plate made of copper topped by a silver layer. Later, “gilding” or “gold toning” was added to preserve, and add warmth to, delicate images.

According to the Library of Congress, the “daguerreian era” lasted just twenty-one years, from the announcement of the process to the early 1860s. Easier and faster methods for capturing images, such as tintypes and ambrotypes, replaced the daguerreotype almost completely. Still, the daguerreotype is credited with enabling individuals to obtain likenesses of themselves and their loved ones for a relatively low-cost, making it extremely popular around the world.

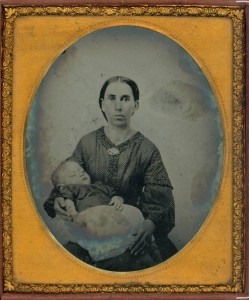

Daguerreotypes were sometimes used as memorials of the deceased, as well. According to this article, daguerreotypes were seen as the most accurate representations of one’s spirit that could be obtained. Death was seen as a moment “when the hypocrisy of a person’s lifetime fell away, and the treasured last words were uttered without earthly motives… A realistic daguerreotype taken just after death might show a ‘beatific’ or even ‘triumphant’ entrance into God’s kingdom.” In fact, Ohio Memory’s collection of daguerreotypes features one such image, seen at right, of a mother and her deceased child. Like many others of her time, the mother may have believed that the portrait reflected her child’s soul, the truest part of him or her.

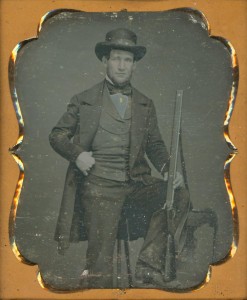

The collection also includes a number of other images: of individuals, of families, and of a home’s exterior. Like the photos of today, each depicts a moment in time and likely became a treasured memento. We hope you’ll take a moment and look through these images. And the next time you take a photo, regardless of the equipment you use, we hope you’ll think of Louis Daguerre, whose work made your pictures possible.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital/Tangible Media Cataloger at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.