The Boy General: George Armstrong Custer

This June 25 will mark the 140th anniversary of the Battle of Little Bighorn, otherwise known as Custer’s Last Stand. Ohioan George Armstrong Custer was many things in his lifetime – teacher, student, soldier – but it was his last, most notorious act for which he is best known.

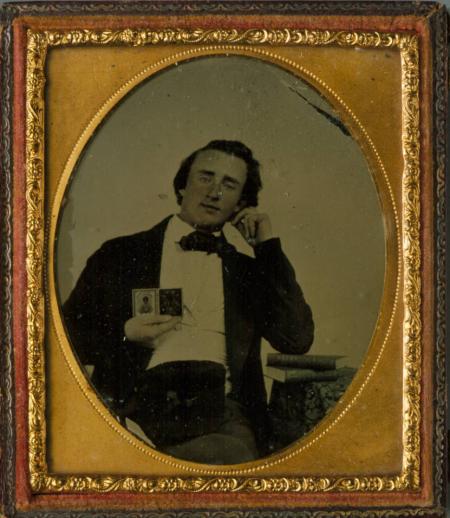

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, in 1839. Though he spent a good portion of his youth in Michigan, he eventually returned to Ohio and graduated from the McNeely Normal School in Hopedale. After graduation, Custer remained in Ohio and began teaching in Cadiz. Teaching, however, appears not to have kept his interest because, soon thereafter, in 1857, he applied to West Point. It was there that he first distinguished himself, not as an exemplary student but as quite the opposite. In each of the years he was in attendance he came very close to being expelled due to excessive demerits, generally earned for playing pranks on fellow students. Custer failed to distinguish himself as a scholar, however, and in fact appeared to be completely unconcerned with his studies. As a consequence, he ranked last in his class when he graduated in 1861.

Custer’s service in the Civil War showed a level of discipline and a quickness to volunteer that was wholly lacking during his school years. He was rapidly promoted over the course of the war, receiving the rank of Brevet Major General by 1865 and earning him the nickname “The Boy General.” After the war ended, Custer took a post in Austin, Texas, as part of the Reconstruction effort. When that post ended, he briefly considered politics but soon returned to military service, with his activities taking him to Indian Territory, which was land set aside by the U.S. Government for the relocation of American Indians who were forcibly removed from their lands.

In 1874, Custer escorted an expedition of gold-seekers into the Black Hills of South Dakota, in violation of the Treaty of 1868, which recognized that the region was sacred to the Lakota and and decreed exclusive use of the area to the Lakota. The discovery of gold there resulted in additional miners entering the area, leaving the Lakota to enforce the restrictions entailed in the treaty on their own. In 1876, in response to the miners’ demands for protection, an Army detachment led by Custer entered the Black Hills and encountered an encampment of Lakota and Cheyenne. Despite being grossly outnumbered by the Lakota-Cheyenne coalition, Custer attacked the group. He and all of his men were killed.

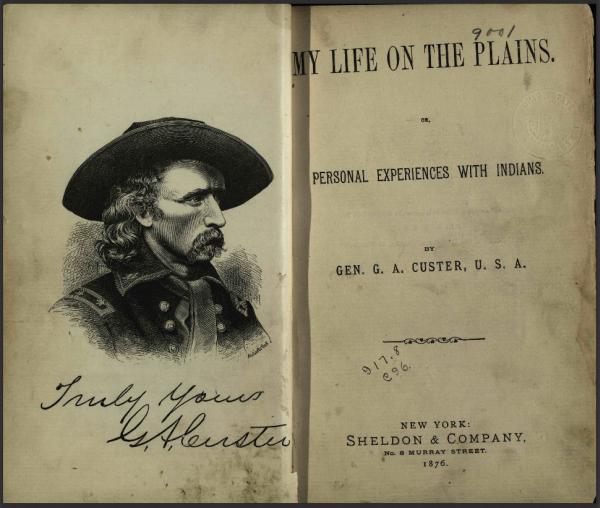

In 1874, two years before his death, Custer published My Life on the Plains. It contains first-hand accounts regarding his time spent in Indian Territory and his interpretations of events during the Indian Wars of 1867 to 1869. The copy you’ll find in Ohio Memory was printed in 1876, the year that he was killed. As one can imagine, Custer’s writings can be seen as problematic, particularly in light of the events surrounding his death and the choices that led to it. The book is peppered with tails of bravado and machismo – qualities that appear to characterize Custer throughout his life – as well as being clearly one-sided and not necessarily a factual and balanced account. The beauty of history is that we are able to revisit texts like My Life on the Plains and gain new insights based on the facts that we have discovered over time. We hope that you will read it as an artifact of the ideologies of one 19th century man and that you’ll look at this part of history in new ways.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.