War Is Hell: William Tecumseh Sherman, Atlanta, and the March to the Sea

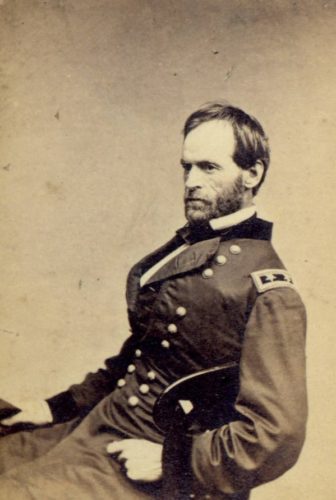

During the final year of the Civil War, Ohio native William Tecumseh Sherman was given command of the Union’s Western Armies as well as a mission: while Ulysses S. Grant engaged Southern forces under Robert E. Lee, Sherman was to advance through the Confederate heartland and capture Atlanta. Although his actions would make him the most hated man in the South, they likely helped hasten the end of the Confederacy and the war.

Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio, on February 8, 1820. His father was a prominent lawyer, but when he died suddenly in 1829, he left his wife and eleven children with limited financial resources. William was raised by family friend Thomas Ewing, who secured him an appointment to West Point.

After graduating sixth in his class, Sherman had several assignments in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina before being stationed in California. He married Thomas Ewing’s daughter Eleanor in 1850 and resigned his army commission three years later. He worked as a banker in California during the height of the Gold Rush and practiced law in Kansas before becoming superintendent of the Louisiana Military Academy in 1859. When Louisiana seceded from the Union in 1861, Sherman resigned and moved to St. Louis. After the Battle of Fort Sumter three months later, he rejoined the Army as a colonel.

Sherman was promoted to brigadier general after the First Battle of Bull Run, and in March 1862, he was assigned to Ulysses S. Grant in the Army of West Tennessee. Their experiences at the Battle of Shiloh formed the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Sherman commanded troops at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, and after Grant was promoted to commander of all U.S. Armies in early 1864, he promoted Sherman to commander of all troops in the Western Theatre.

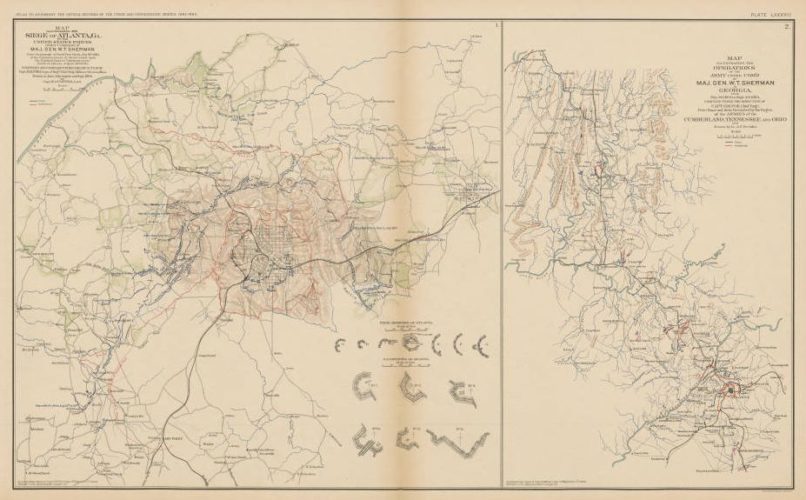

By 1864, Sherman had come to believe that a Union victory required not only defeating the Southern armies, but also destroying the South’s physical ability and psychological will to continue the war. Atlanta, a transportation and industrial center and symbol of Confederate strength, made a prime target. After a four-month campaign against Confederate generals Joseph E. Johnston and John B. Hood, Sherman captured the city on September 2, 1864, (thereby assuring Abraham Lincoln’s re-election two months later). Union forces occupied the city until mid-November as Sherman carefully planned his “March to the Sea.” Before leaving Atlanta he ordered his engineers to carry out the destruction of targeted buildings that could have helped the Southern war effort. However, soldiers also set unauthorized fires, culminating on November 15, when Union troops set much of the downtown area ablaze during their last night in the city.

Sherman sent half his army to Nashville to engage Confederate forces under Hood. He divided his remaining 62,000 troops into two columns that marched thirty miles apart and set out for Savannah. Sherman had carefully studied census records to make sure his troops could live off the land before leaving Atlanta—and his supply line. The Union soldiers raided farms, destroyed cotton fields and mills, slaughtered livestock, burned properties where they met resistance, and took as much food as they could carry. Their march had the desired effect of instilling fear and uncertainty across the Georgia countryside.

On December 21, 1864, Sherman presented the city of Savannah to Abraham Lincoln as an early Christmas gift. He then turned north, chasing and eventually defeating Joseph Johnston’s forces at the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina. On April 26, 1865, Sherman accepted the surrender of Johnston and all Confederate troops in Georgia, Florida, and the Carolinas. It was the single largest troop surrender of the Civil War. After the agreement was signed, Sherman ordered his troops to stop foraging and instructed Union commanders to loan captured mules and wagons to local families to help with spring planting.

When Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1869, Sherman became commander of the U.S. Army, a post he held until his retirement in 1886. He died in New York City on February 14, 1891, just a few days after his 71st birthday. Joseph Johnston, who had become close friends with Sherman after the war, traveled to New York and stood in the rain for the funeral. He contracted pneumonia and died just two weeks later.

During the occupation of Atlanta, Sherman wrote to city officials that “war is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” Years later, he shortened this sentiment during an address at the Michigan Military Academy: War is hell.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.