Ohio Goes West: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915

August 1914 marked the opening of the Panama Canal, an engineering feat that halved shipping time between America’s coasts. In 1915, the city of San Francisco invited the world to celebrate.

In the 19th century, ships carrying goods from the East Coast to the West Coast had to sail down the eastern coast of North and South America, navigate the dangerous waters of Cape Horn, and sail back up the western coast of both continents. The narrow isthmus of Panama was seen as the best option to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and cut valuable time off the trip. A French company started the project in the 1880s, but went bankrupt after suffering a string of engineering problems and losing nearly 20,000 lives to tropical diseases. Teddy Roosevelt made the canal a priority when he took office in 1901, and after a series of political maneuvers, the U.S. secured building rights from the newly-independent Republic of Panama in 1903. Ohioan William Howard Taft assumed oversight of the project as Roosevelt’s secretary of war.

In 1904, a group of powerful San Francisco merchants proposed hosting a world’s fair to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. They requested federal seed money, but progress stalled as Congress delayed its decision. On April 1, 1906, an earthquake and subsequent fires decimated the city. As they began rebuilding, the merchants and city officials didn’t lose sight of the fair, and in December of that year they created the Panama-Pacific Exposition Company to make it happen. After four years of fundraising and an extensive public relations campaign, San Francisco beat out competing cities by promising not to accept federal funds for the project. On February 15, 1911, now-President Taft signed a resolution naming San Francisco as the official location of the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition.

After considering several sites, the Company chose the Harbor View area (now the Marina District) because of its views of the bay. The 630-acre site stretched along nearly three miles of waterfront from the Presidio to Fort Mason. Although the location was relatively undeveloped, the Company still had to buy 75 city blocks, demolish 200 buildings, fill in marshland, and get permission to build on U.S. Army land at the Presidio and Fort Mason.

The Company assembled a team of nationally-known architects, landscape designers, and engineers to plan and construct the exposition. The buildings were designed to look like Italian marble, but because they only needed to last eleven months, they were built with a plaster mixture over wooden frames. More than 1,500 statues were created using the same plaster mixture, and more than 30,000 full-grown trees were shipped in to complete the lavish gardens.

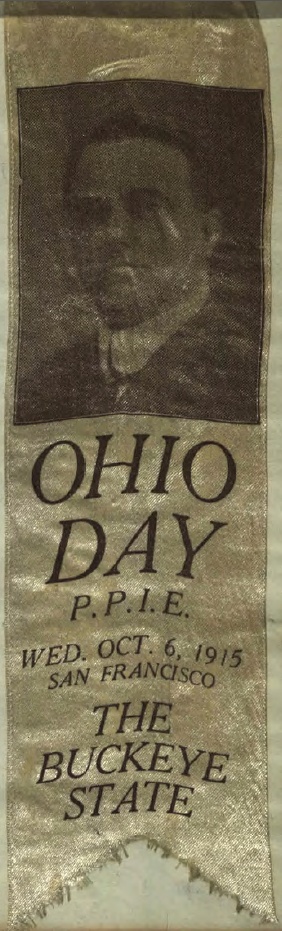

In Ohio, the General Assembly passed legislation establishing the Panama-Pacific International Exposition Commission to oversee the state’s participation in the fair. The Commission contracted an architect and construction company to design and build the Ohio Building, hired staff, and arranged exhibits of Ohio products to be featured at the fair.

The exposition opened on February 20, 1915. Nearly 150,000 residents and visitors joined the opening day parade through the city streets, and at noon, President Woodrow Wilson pressed a gold telegraph key in Washington, D.C., that opened the gates and welcomed people to the fair. Visitors were greeted by the Tower of Jewels, a 435-foot structure (the tallest in San Francisco at the time) covered with more than 100,000 colored glass gems, illuminated at night by powerful floodlights. The gems were hung on small brass hooks, which allowed them to sway in the ocean breeze and make the entire building sparkle. The exposition’s official nickname, “The Jewel City,” was suggested by twelve-year-old Virginia Stephens (who later went on to become the first African American woman admitted to the California bar).

Through the Tower of Jewels was a large courtyard surrounded on all sides by the exhibition palaces. The Fine Arts Palace was located on the west end of the court (flanked by palaces related to education, agriculture, and the liberal arts), and the Machinery Palace stood on the east end (flanked by palaces related to transportation, manufacturing, and mining). Each palace was designed to showcase human culture and achievement. In the Palace of Transportation, Henry Ford displayed an entire assembly line that produced a new car every ten minutes, and Maria Montessori ran a fully-functioning classroom in the Palace of Education. In the Liberal Arts Palace, guests could place a transcontinental telephone call for the bargain price of $20.70 for the first three minutes. The Palace of Fine Arts was surrounded by a lagoon and gardens that gave visitors a quiet space in the otherwise noisy exposition. Although World War I prevented many countries from actively taking part in the fair, at least fourteen countries were represented by more than 11,000 works of art.

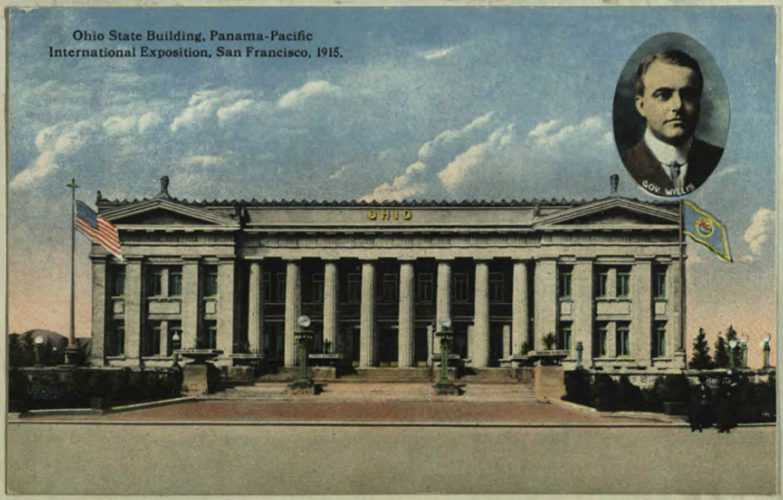

Twenty-five states and the city of New York constructed buildings along the Avenue of the States, which was located on the Presidio. Many of these buildings featured items produced in each state as well as information and exhibits about the state’s history and culture. The Pennsylvania Building housed the Liberty Bell, which made a cross-country trip to appear at the exposition. The Ohio Building was inspired by the Ohio Statehouse (minus the dome), and its first floor provided spaces where current and former Ohioans visiting the fair could relax, mingle, and catch up on news from home. The building also included an office, guest suites, dining areas, and spaces suitable for hosting receptions and receiving visiting dignitaries.

In addition to state buildings, the Presidio was also home to the foreign pavilions. In 1911, President Taft had invited the nations of the world to participate in the exposition. Although World War I greatly reduced the scope of this participation, ultimately 31 nations were represented in 21 international pavilions that contained exhibits and demonstrations highlighting each country’s culture. To see rare color photos of several fair buildings, visit the National Museum of American History here.

When the exposition closed on December 4, 1915, more than 18 million people had visited the fair, and the Company had made a $1.3 million profit on its $25 million total investment. To clear the site for new development and generate more revenue, the Company sold nearly every building, fixture, and plant.

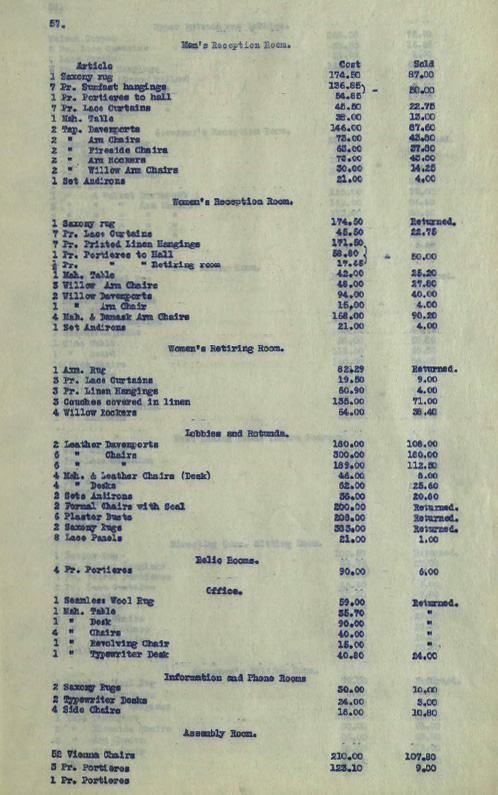

Like the Company, the Ohio Commission sold as many exposition assets as it could, from the Ohio Building’s furniture to its vacuum cleaner. The building itself was sold to a group of investors for $1,000 and moved by barge to San Mateo, where it was intended to serve as the clubhouse for a country club. When the investors ran out of funds, the building sat empty for several years. Prohibition presented a new opportunity, and the former Ohio Building became a speakeasy called the Babylon Club. When police shut down the operation, it again sat empty until the owner of a neighboring airport bought it and used it as workshop. When he eventually sold the airport in 1956, the new owner burned the building to the ground.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition not only celebrated the Panama Canal, but also showed the world that San Francisco had successfully risen from the ashes of the 1906 earthquake. Although the exposition was never intended to last, traces of it can still be seen in the city today. The Palace of Fine Arts was saved due to the efforts of Phoebe Apperson Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst). Businessman Adolph Spreckels and his wife Alma admired the French Pavilion so much that they gave the city an exact replica, which is used as a WWI memorial and art museum. Marina Green and Crissy Field are located on former marshland that was filled in for the exposition. However, not all of the filled land survived; in 1999, the National Park Service restored parts of the exposition site to their original tidal marshlands, which now provide habitat for hundreds of plant and animal species.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.