William Henry Harrison: Soldier and Statesman

William Henry Harrison, the ninth president of the United States, was not only the last president born a British subject and the first sitting president to have his photograph taken, but also the first president to call Ohio home. Harrison was born February 9, 1773, and was the youngest of seven children in a Virginia plantation family. His father, Benjamin Harrison V, signed the Declaration of Independence and served three terms as governor of Virginia. William was educated by private tutors, studied classics and history in college, and then began to study medicine at his father’s insistence. However, Benjamin’s death in 1791 left William without funds, and he exchanged school for a military career.

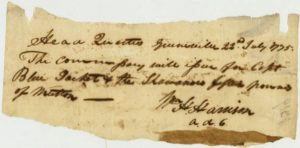

Harrison obtained a commission as an ensign in the Regular Army and was deployed to Fort Washington, near present-day Cincinnati. He was soon promoted to lieutenant and served as aide-de-camp to General “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Harrison participated in Wayne’s victory against the American Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and signed the Treaty of Greenville as a witness. (Wayne was the principal negotiator.) These two events opened up roughly two-thirds of present-day Ohio to European settlement. After Wayne’s death in 1795, Harrison, now a captain, took command of Fort Washington. That same year, he eloped with Anna Tuthill Symmes of nearby North Bend, Ohio (whose father strongly disapproved of the marriage). The two would go on to have ten children, although only four of them would live to see Harrison in the White House.

In 1798 Harrison resigned from the Army and, thanks to his father-in-law’s Washington contacts, was appointed secretary of the Northwest Territory—land that would eventually become present-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and northeastern Minnesota. Harrison was narrowly elected the territory’s first delegate to Congress. Although his position was nonvoting, he helped pass legislation that made it easier to buy small tracts of territorial land at low cost, thereby promoting settlement.

When the Northwest Territory was divided in 1800 to prepare for Ohio’s statehood, Harrison became governor of the Indiana Territory (present-day Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, western Michigan, and northeastern Minnesota). One of his main responsibilities during his twelve-year tenure was securing legal claim to as much American Indian land as possible, thereby increasing the non-Indian population enough to attain statehood. Harrison completed seven treaties with tribal leaders between 1802 and 1805; in the largest of these, he convinced five minor Sac chiefs (after plying them with alcohol) to sign away 51 million acres for the price of one penny per 200 acres.

Tecumseh, a leading American Indian chief in the region, became increasingly frustrated by the growing European settlement and began building alliances with other chiefs, negotiating with the British Army, and conducting raids against outlying settlements. In 1811, Harrison led nearly 1,000 Regular Army, militia, and volunteers in a strike against Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa, while Tecumseh was away recruiting allies for his confederation. On November 6, Harrison made camp near the Tippecanoe River, but Tenskwatawa’s forces discovered their location and attacked before dawn the next day. Harrison ordered a successful counterattack, but lost nearly twenty percent of his troops in the process. Despite this, public reaction to the battle was generally favorable, and Harrison’s fame began to grow.

By autumn of 1812, Harrison had rejoined the Army and achieved the rank of major general. He commanded all forces in the Northwest, but much of the territory had fallen under British control during the early months of the War of 1812. The tide turned with Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory at Lake Erie the following year; after retaking Detroit, Harrison’s troops pursued the British and American Indians as they moved north. The two armies met at the Thames River in what is present-day Ontario, where Harrison’s troops outnumbered opposing forces nearly three to one. The British general fled, and Tecumseh was killed, permanently ending the alliance he had built.

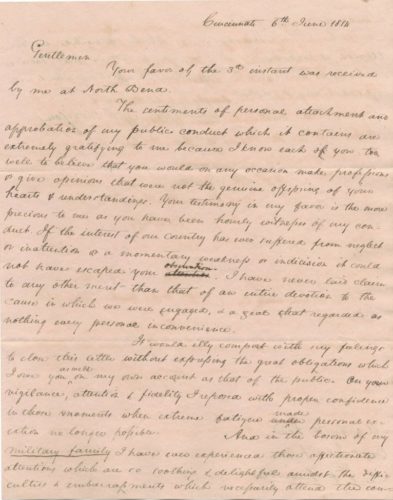

The victory at Thames River not only boosted U.S. morale, but also cemented Harrison’s fame. Instead of continuing to fight the British in Canada, he took a leave of absence from the Army and toured New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, attending receptions held in his honor. Harrison resigned from the Army in May 1814 (before the war’s end) and settled on a farm in North Bend.

After the war, Harrison was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (1816-19), the Ohio Senate (1819-1821), and the U.S. Senate (1824-28). In 1836 he was one of four Whig party candidates nominated for president—a deliberate strategy by the Whigs to deny Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren the electoral college and force the House of Representatives to decide the outcome. However, the plan failed, and Van Buren won the election.

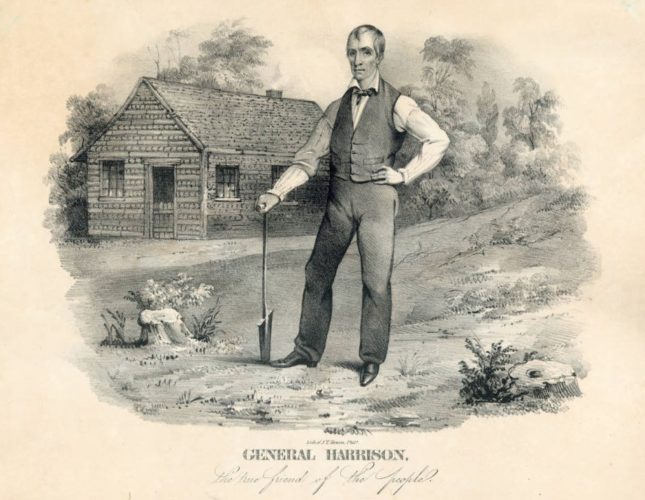

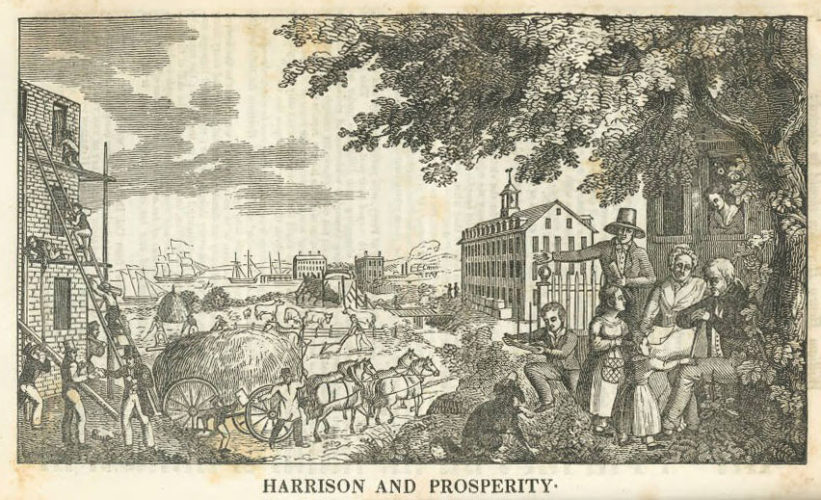

In 1840, Harrison was the only Whig candidate, with John Tyler as his running mate. Van Buren was unpopular due to his mismanagement of the 1837 financial crisis and his aloof, aristocratic demeanor. The Whigs believed they could win the election if they could provide a candidate that contrasted with the distant Van Buren. They therefore mounted the first modern election campaign, re-making the image of their college educated, plantation-born candidate into a man of the people. The Democrats made a fatal error by trying to portray Harrison as a simple old man who would rather sit in his log cabin drinking hard cider than run the country. Harrison promptly adopted the log cabin and hard cider as campaign symbols, and the Whigs flooded the voting populace with posters, memorabilia, and campaign rallies. Harrison actively campaigned with the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too”; a rally at the site of the Battle of Tippecanoe drew 60,000 people. Harrison won the election, receiving nearly four times as many electoral votes as Van Buren.

Harrison took the oath of office on March 4, 1841, a cold and rainy day. He gave the longest inaugural address in presidential history; at nearly 8,500 words, his speech lasted almost two hours. Roughly three weeks later, Harrison caught a cold that apparently developed into pneumonia, and on April 4, 1841, he became the first president to die in office. (Although Harrison’s doctor listed pneumonia as the cause of death, a 2014 analysis suggested that he may have died from septic shock caused by a contaminated water supply.) Harrison’s funeral took place in Cincinnati on April 7, 1841. After being interred in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., his remains were moved to his home in North Bend.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.