Are You an “American” or a “Hun”?: Anti-German Hysteria during World War I

During World War I, anti-German feeling and activity spread throughout the United States, in large part as a way to show support for the American war effort. Germans were the largest non-English-speaking minority group at the time of the 1910 census—in Ohio, the German-American immigrant population was over 200,000 by 1900, with even more Ohioans claiming German ancestry. This made Ohio particularly vulnerable to anti-German sentiment, and the impact on German-Americans in the state was long-term.

Public policy shaped many of Ohio’s anti-German activities. During the war, the Ohio State Council of Defense established an Americanization Committee led by Western Reserve University Professor Raymond Moley. The group’s official charge was to assist immigrants in learning English and American values so that they could become U.S. citizens, but it went beyond this work and censored what it considered “pro-German” reading material. Many schools limited or stopped teaching German language and literature as well, and teachers had to take loyalty oaths. In 1919, the Ake Law (later declared unconstitutional) made it illegal to teach German in any school below eighth grade.

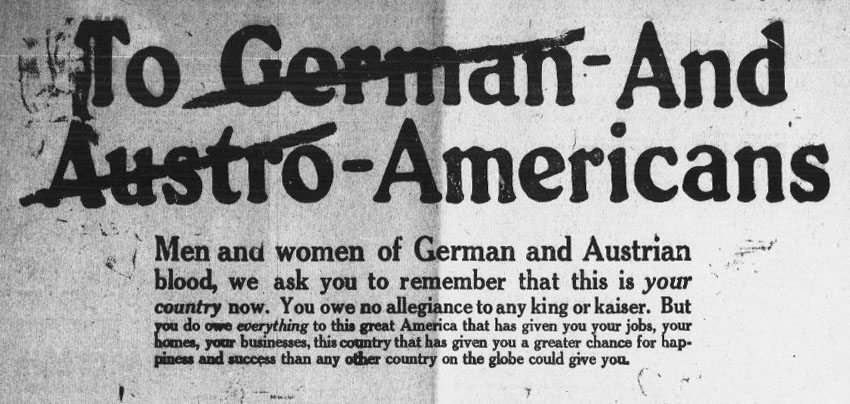

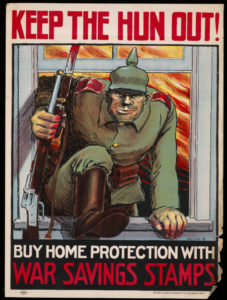

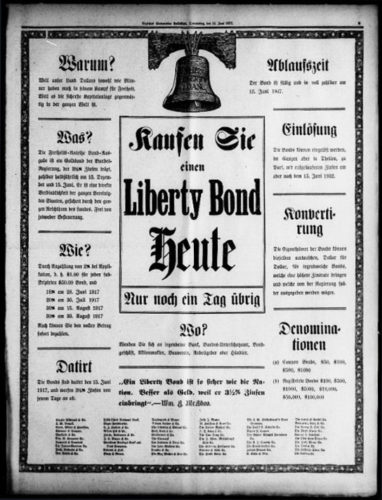

Governor James A. Cox’s own strongly anti-German attitudes only increased the hysteria across Ohio. Most German-Americans actually supported the U.S. throughout WWI, purchasing war bonds and rationing resources along with the rest of the American population, but the fierce and widespread anti-German sentiment they experienced prompted some to become increasingly pro-German as the conflict went on. Posters, speeches and newspaper articles portrayed Germans as barbaric and evil, and German-Americans were looked upon with suspicion. Some, like Austrian-born Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra conductor Ernst Kunwald, were even persecuted for alleged spying, sedition or other acts of treason.

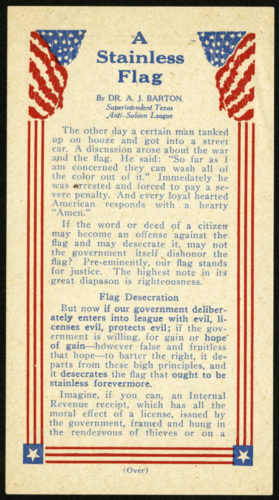

German-American businesses, particularly beer breweries, lost customers. Prohibitionists took advantage of anti-German feeling, emphasizing the importance of redirecting wheat to the war effort over beer manufacture. The American Issue, a newspaper of the central Ohio-based Anti-Saloon League, published a number of cartoons connecting the evils of Germans with the evils of alcohols. Some businesses were able to recover, but many others were not. Prior to the war, German-American newspapers had been considered the best of the country’s immigrant press, but a loss of patronage and advertisements caused many, including the Cincinnati Volksblatt and the Columbus Express and Westbote, to permanently cease publication.

Anti-German sentiment manifested in other ways as well. Germans were unflatteringly nicknamed “Huns” and “Fritzies.” Hamburgers were temporarily referred to as “liberty sandwiches” and sauerkraut as “liberty cabbage.” Towns and streets with German names were renamed—New Berlin became North Canton, and in Cincinnati, German and Berlin Streets became English and Woodward Streets. Even dogs were not immune to harassment: dachshunds, or “liberty pups,” the Kaiser’s favorite dog breed, were “virtually driven off the streets of Cincinnati.” Some German-Americans Americanized their names (Schmidt to Smith, Mueller to Miller, etc.), reduced the amount of German they spoke in public, and made their cultural and religious activities increasingly private affairs. Ultimately, this hysteria led to the further assimilation of German-Americans into American life.

Learn more about anti-German sentiment in the World War I in Ohio Digital Collection and in Ohio’s digital newspaper collections on Chronicling America and Ohio Memory, and check out our German-American Experience During World War I lesson plan.

Further reading:

- Ohio and Its People by George Knepper (2003)

- German-Americans and the World War by Carl F. Wittke (1936)

- Ohio’s German Language Press and the War by Carl F. Wittke (1919)

Thanks to Jenni Salamon, Coordinator for the Ohio Digital Newspaper Program, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.