The End and the Beginning of an Age: American Children in World War I

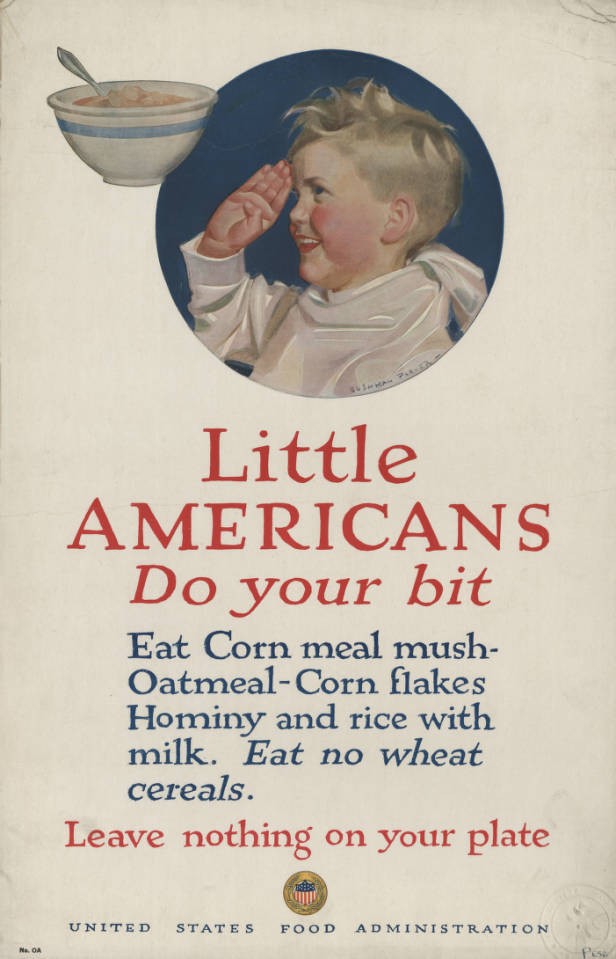

For American children in World War I, life on a home front far from battle did not mean life lived far from the effects of war. Citizens of every age and ability were called upon to assist in the war effort, and children were no exception. From gardening to raising funds to sacrificing at home, American kids answered the call, making a significant contribution to their country and demonstrating considerable patriotism and self-sacrifice.

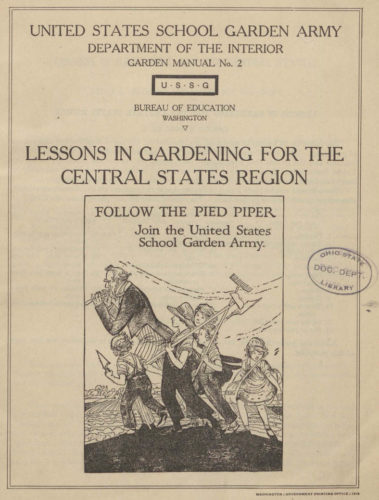

In America, “19th century views on the benefits of fresh air, physical exertion, and character building, as well as the basic educational aspects of nature study… ignited the school garden movement.” However, with the advent of war, gardening became a patriotic activity. Citizens were urged to utilize all available land, including school grounds, to grow produce that could combat food shortages at home and abroad. The Bureau of Education created the U.S. School Garden Army (USSGA), enlisting children to be “soldiers of the soil” and utilizing the motto “a garden for every child, every child in a garden” to encourage participation.

They supported gardening and food preservation efforts by publishing pamphlets which included lessons on cultivating a variety of produce, building cold frames for growing in lower temperatures, and recipes for canning and drying foods. The USSGA logo featured the Pied Piper, who plays a flute while children carrying garden tools happily follow behind him, ready to do their part for America.

Youth organizations responded to the call for help through volunteerism and fundraising. Girl Scouts volunteered as ambulance drivers for the Red Cross, knit scarves and other items for soldiers, and sold war bonds, as did the Boy Scouts and the Junior Red Cross, which was established in response to the war. Contributions by youth organizations were quite remarkable: upon the request of President Woodrow Wilson, the Boy Scouts harvested 109,250 black walnut trees, which were used for propellers and gun stocks, and planted three more trees for each one cut down. Meanwhile, the Junior Red Cross raised over $3.6 million over the course of the war.

Education of children in America changed substantially during the war. Woodrow Wilson’s administration published a series of print materials focusing on nationalism and patriotism, such as the previously-mentioned materials for the USSGA, and also promoting anti-German sentiment. Curriculum was adjusted to reflect our alliance with Great Britain, with textbooks being re-written to downplay friction between Great Britain and the American colonies. In an effort to promote unification across the country, education was nationalized, keeping curricula consistent across states.

Children’s activities were not limited to the school yard or youth organizations, either. With male breadwinners fighting in, or dying as a result of, the war, women found themselves working for wages to support their families or to fill holes left by absent men. For women, these activities contributed to increased rights, such as suffrage. For children, however, this meant a change to the family dynamic that resulted in less time spent with parents and an expectation that they would help at home, filling roles previously held by adults. It also meant lessons in thrift, and considerable sacrifice, that children may not have been exposed to otherwise. This, along with the government’s call for children to help with the war effort, meant, quite simply, that children were forced to grow up quickly.

American participation in World War I was relatively brief; we declared war in April of 1917 and fought for 19 months, when Armistice ended the war on November 11, 1918. American sacrifice, however, was substantial and life-changing for families. 16,516 Americans were killed, either in battle or by illness; 320,000 were either injured or sickened; countless women, including mothers acting as single parents in their husbands’ absences, were called upon to fill roles previously held by men. As a consequence, the war was life-changing for hundreds of thousands of children throughout the country.

In Mr. Britling Sees It Through (available externally in full-text from Project Gutenberg), H.G. Wells wrote of the war that “this is the end and the beginning of an age.” For American children growing up during World War I, no truer words have been spoken.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Note: Guidelines for canning fruits and vegetables have been revised since the publication of the pamphlets linked in this post. For updated information and current safety guidelines, please visit the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Complete Guide to Home Canning: https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/publications_usda.html.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.