Sarah Margru Kinson, Child of the Amistad

In February 1839, in violation of international treaties, slavers took a group of Africans from Sierra Leone to Cuba. Most had been kidnapped outright, but a few had been captured in war or, like a young girl named Margru, sold into slavery to pay a debt. In Cuba, two plantation owners purchased 53 of the enslaved Africans (49 adults and four children, including Margru) and set sail for their Caribbean plantation on the schooner Amistad. The events that followed involved two U.S. presidents and a legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

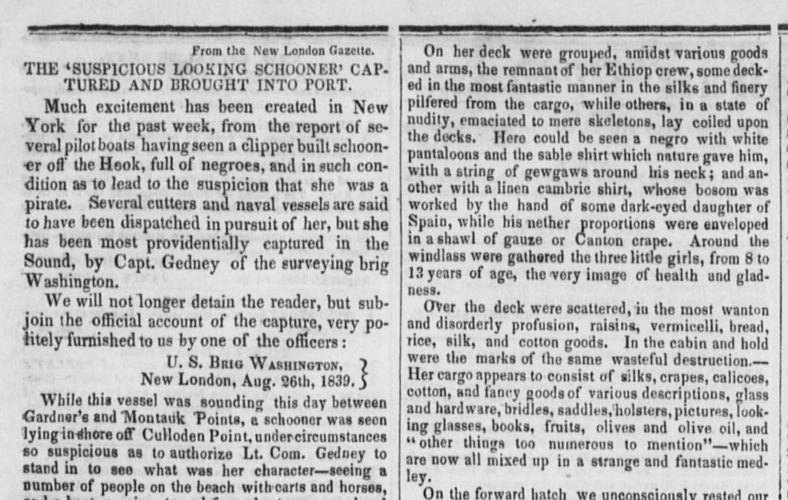

A few days after leaving port, the Africans on board took control of the Amistad, killed the captain and the cook, and ordered the plantation owners to sail back to Africa. Instead, they sailed east toward Africa by day, but sailed north and west by night. They eventually reached the waters off Long Island, New York, where the ship’s wandering path and ragged appearance had caused suspicion. There, the Amistad was seized by the U.S. Navy brig Washington and towed to New London, Connecticut; the enslaved individuals were jailed in New Haven and charged with mutiny and murder.

The story of the Amistad quickly became a national sensation. Crowds flooded New Haven, hoping to catch a glimpse of the captives (one local resident made sketches of the captives, including Margru, that survive today), and abolitionists saw the media frenzy as an opportunity to draw attention to their cause. After visiting the captives in jail, Lewis Tappan, a prominent New York abolitionist, helped organize a committee to raise money for lawyers and arranged for the four children, including Margru, to stay at the jailer’s house.

Although the murder charges were soon dropped, the Africans remained jailed as multiple parties argued over their fate. The captain of the Washington claimed salvage rights to the Amistad’s cargo, including those on board. The plantation owners also claimed the enslaved Africans and ship’s cargo as property. The Spanish government, with the support of U.S. President Martin Van Buren and the U.S. attorney, claimed that a 1795 treaty between the two nations required all property (including the captives) to be returned to Cuba, where the Africans would surely have been put to death. At issue in all the claims was the question of whether the Africans were property or free people who had been illegally enslaved. In January 1840, the federal court ruled that the Africans were not property because they had been sold into slavery in violation of international law. Expecting a different outcome, Van Buren had a ship waiting to rush the Africans back to Cuba. Instead, he ordered an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Arguments didn’t begin until February 1841. Former president John Quincy Adams, at age 73, spoke on behalf of the Africans for eight and a half hours, arguing that because they had been kidnapped and transported illegally, they had never been slaves. In March 1841, the Supreme Court agreed by a vote of 8-1 (despite the fact that five of the nine justices owned or had formerly owned slaves) and ordered the release of the 35 survivors. The rest of the original 53 had died either at sea or in jail awaiting trial.

After the trial, Tappan and others continued to raise funds with the goal of returning the Amistad survivors to Africa. Survivors were moved from the New Haven jail to an abolitionist community in Connecticut and given anglicized names, and it was there that Margru was renamed Sarah Kinson. In November 1841, the Amistad survivors and five Christian missionaries set sail for Sierra Leone.

After reaching West Africa the missionaries established the Komende Mission. Although most of the Amistad survivors rejoined their families, a few stayed at the mission, including the four children. The head of the mission, William Raymond, wrote letters to Lewis Tappan that often contained news of Sarah’s accomplishments.

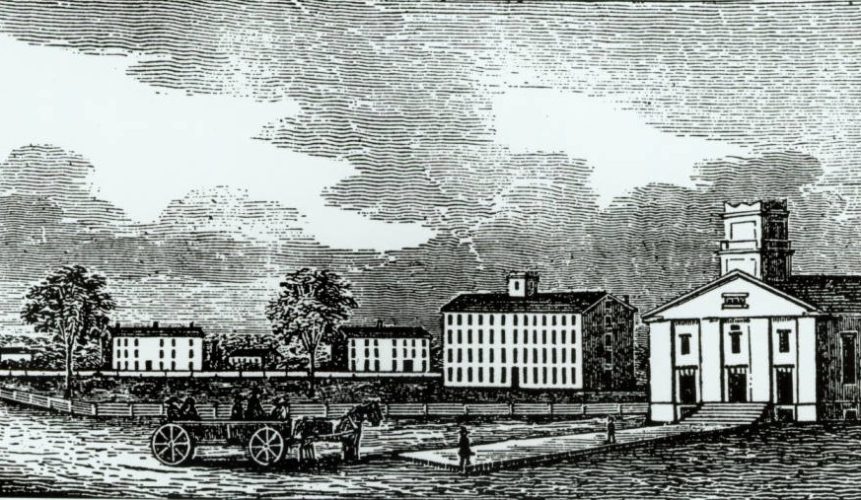

In the summer of 1846, Sarah returned to the U.S. and traveled to Oberlin, Ohio, to further her education. The town had a strongly abolitionist population, and Tappan and his brother had been early benefactors of the Oberlin Collegiate Institute (later renamed Oberlin College). Sarah began preparatory classes in August 1846, and was admitted to Oberlin’s Female Department in 1848, where she began college-level courses (and was likely the first foreign female college student in the country). A great deal of correspondence to, from, and about Sarah exists from the three years she spent at Oberlin. Letters reveal that she excelled at her studies and was respected by teachers and classmates, but was homesick for Africa and eager to return there. You can see a drawing of Sarah from her time at Oberlin here.

Sarah returned to Western Africa in November 1849, where she worked as the schoolmistress of the mission’s girls’ school. Three years later she married Edward Green, an African who had also converted to Christianity. In 1855 the Greens left Komende to start their own mission station, but Edward was accused of adultery and subsequently fired; at this point Sarah’s name disappears from the historical record. The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary General Catalogue of Oberlin College, published in 1909, states that she died in 1858 in Sierra Leone. However, other sources suggest that she remarried and had a son, or lived a long life as a teacher. Regardless of when she died, her remarkable life is remembered.

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

To learn more, you can view images of original documents related to the Amistad at the National Archives and Tulane University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.