A Nation Weeps: The Death of Ulysses S. Grant

Monday, July 23, marks the anniversary of the death of Ulysses S. Grant, Civil War hero, 18th President of the United States, and Ohioan by birth. Grant’s military and political careers are well known: he is credited for having turned the tide toward a Northern victory, defeating Confederates and receiving Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse; he was a two-term president, winning the electoral vote by a large margin both times; and he was well-respected by Americans who were so moved by his contributions that they were known to send him cigars by the thousands and money when he was in need. It is the period leading up to his death, however, that we would like to focus on today, as it exemplifies the tenacity and love for family that made Grant the remarkable man he was.

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant, a tanner and merchant, and Hannah Simpson. He was the oldest of six children and, according to biographer Ron Chernow, was doted upon by his father, who ensured that Grant received an education: “I never missed a quarter of school from the time I was old enough to attend till the time of leaving home,” Grant said in his memoirs (v. 1, p 25). His father, in fact, was the driving force behind his attendance at West Point, initiating contact with the congressmen who nominated Grant for admission to the military academy. One of the congressmen, Thomas Hamer, mistakenly listed his name as “Ulysses S. Grant,” and though Grant was not thrilled – he told his wife, Julia, “you know I have an ‘S’ in my name and don’t know what it stand[s] for” (Chernow, p. 18) – kept the name nonetheless, earning him the nicknames “Uncle Sam,” “Sam,” and, as a Union general during the Civil War, “Unconditional Surrender.”

Grant’s pride and refusal to surrender was a trait that he maintained throughout his life. His values pushed him to honor his commitments and do what he knew to be right, even when doing the opposite might have been easier. His lack of business acumen led him to frequent financial struggles throughout his adult life, but he avoided taking assistance whenever possible. When his brother-in-law gifted him with a slave, Grant, who was anti-slavery, freed the man rather than selling him for the $1500 he likely could have received, simply because he believed it was the right thing to do.

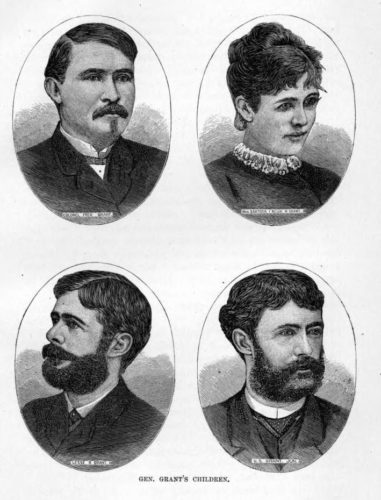

Later, in 1884, Grant faced what was the biggest financial crisis of his life, and still remained steadfast in his desire to do what was honorable. Ferdinand Ward, business partner to Grant’s son, Ulysses S. “Buck” Grant Jr., was found to have been running a Ponzi scheme, soliciting investments from Grant’s friends, speculating with the funds, and then altering the books. When the scheme collapsed, a desperate Grant – who had also invested his savings in the business – approached William Vanderbilt, the wealthiest man in the world and a personal friend, and asked for a loan to save his son. Vanderbilt agreed. Grant then gave the money to Ward so the business could be saved, but Ward pocketed the money and escaped. Though Vanderbilt offered to forgive the loan, Grant refused, and repaid Vanderbilt by giving him his Civil War mementos (you can read more about this story and see images of the Grant mementos, at the Smithsonian National Museum of History’s blog). Grant had rescued his family from poverty, just barely, but more bad news was to come.

That same year, on June 2, Grant, a habitual cigar smoker, experienced severe throat pain after biting into a peach. According to Chernow (p. 928), his pain was so excruciating that his wife initially thought he had swallowed a stinging insect along with the peach. After an initial consultation with a doctor who was visiting Grant’s neighbor, a growth was discovered on the roof of Grant’s mouth, a prescription for pain medication was given and Grant was told to see his family physician as soon as possible. Grant, however, put off the visit until November of that year; when the cancer diagnosis came, it was terminal.

Grant, recognizing the dire situation in which he would be leaving his wife – their finances were still in shambles – made the decision to publish his memoirs. He had been writing articles for a magazine, the Century, and had discovered a love of, and talent for, writing that now motivated him to seek a publisher. If his memoirs could fetch enough money, Julia might be taken care of. The Century agreed to publish the works, and Grant was prepared to partner with them, when Mark Twain came upon the scene. A longtime friend of Grant, Twain had tried to persuade Grant to write his memoirs years before but Grant disliked braggarts and, believing memoirs to be a sign of braggadocio, had declined. Now, Grant was ready to write, and Twain, who had formed a publishing company and who had recently published Huckleberry Finn, was interested. Upon reviewing the contract the Century had drawn up and the 10% advance they had offered Grant, Twain was appalled, saying that the Century’s terms were “simply absurd and should not be considered for an instant” (Chernow, p. 935). Grant balked. He had already given a verbal agreement to the Century and, as previously noted, he was nothing if not honorable and ethical. Twain reminded him that he had actually approached Grant first regarding his memoirs, and then made an offer that Grant simply could not refuse: a 20% royalty or 70% of net profits and $50,000 on the spot (Chernow, p. 935).

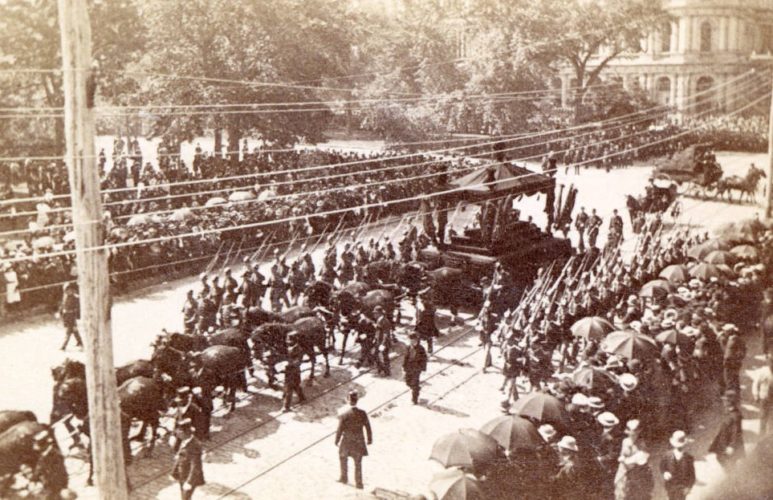

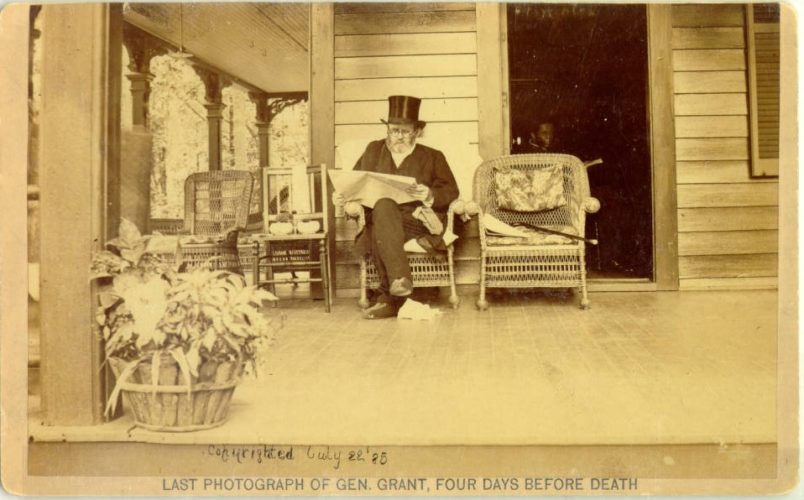

Grant’s remaining days were spend furiously writing what would be a two-volume set, sold by subscription, highlighting his early life and his days in the military and omitting personal stories beyond those from his very early years. Chernow (p. 939) relates that the work he turned out was seen as remarkable, copied clearly, written concisely, and needing little editing beyond grammar and punctuation. He worked tirelessly, for hours each day, through pain and exhaustion. At the end, he was unable to speak, eat, or drink, yet he continued writing, completing his memoirs on July 16, 1885. Extremely ill, he died a week later, on July 23. Upon his death, president Grover Cleveland’s proclamation (found here on page one of the Van Wert Times, Friday, July 31, 1885) read, in part:

In making this announcement to the people of the United States the President is impressed with the magnitude of the public loss of a great military leader, who was in the hour of victory magnanimous, amid disaster serene and self-sustained; who in every station, whether as a soldier or as a Chief Magistrate, twice called to power by his fellow-countrymen, trod unswervingly the pathway of duty, undeterred by doubts, single-minded and straightforward.

The memoirs were, ultimately, a tremendous success, selling over 300,000 two-volume sets and providing Julia Grant with $450,000 in royalties. One set is owned by the State Library of Ohio and is held in the Rare Book Room; we welcome those who are interested to visit and see this labor of love in person. The State Library also holds a copy of Grant, the 2017 Ron Chernow biography upon which this piece heavily relies. The Ohio History Connection has a number of holdings relating to Grant, including published works, archival materials, and physical objects. Numerous images can be found on Ohio Memory, as well, including photos of Grant’s birthplace and childhood home, the room in which he did much of his writing after falling ill, and a family portrait taken just a month before his death.

Ohio’s heroes are many, as are our presidents. This Monday, take a moment to remember an Ohioan who was both hero and president, who dedicated his life to service of his country and his loved ones.

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Learn even more about the life and legacy of Ulysses S. Grant at his birthplace in Point Pleasant and boyhood home in Georgetown, both Ohio History Connection sites.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.