“An Absolute Cure”: The Golden Age of Patent Medicine

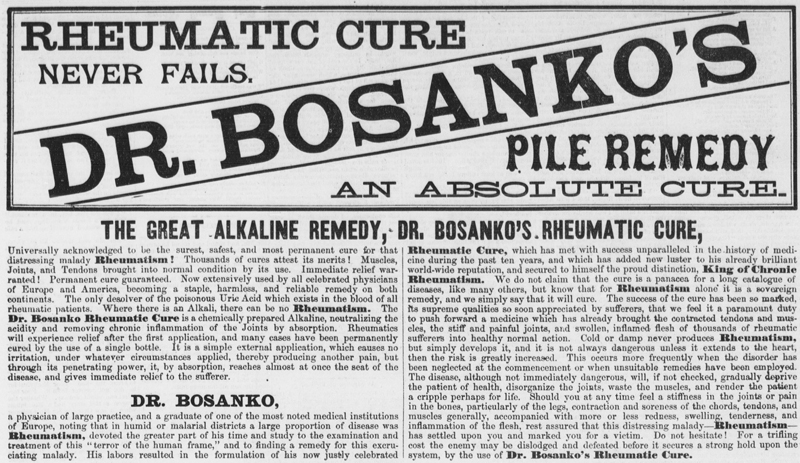

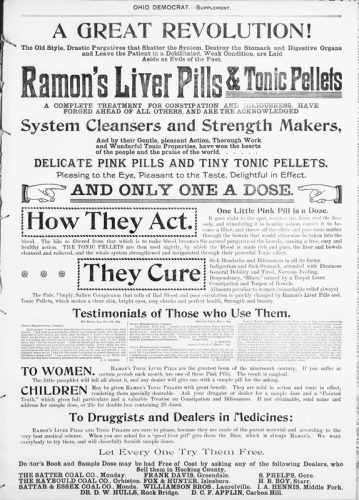

Have you ever looked at an old newspaper and been curious about the variety and number of advertisements for cure-all medicines? The mid-19th century through the early 20th century was the “golden age of patent medicines.” Compounds, pills, pellets, syrups and ointments promised to cure a variety of ailments, and in a time when hospitals and doctors were not always trusted, these quick and often cheap remedies were extremely popular. These products were also among the first to pioneer modern advertising and sales strategies including client testimonials and exaggerated (or even false) claims about their efficacy.

One popular medicine, Peruna, was developed just south of Columbus, Ohio, by Dr. Samuel B. Hartmann. It was supposed to cure and prevent catarrhal disease (congestion) which, according to one advertisement, “pervades every part of the human body” from head to nose to lungs to liver. Hartman’s sales campaign involved full page newspaper ads filled with product information and guarantees, as well as endorsements from both prominent and regular citizens.

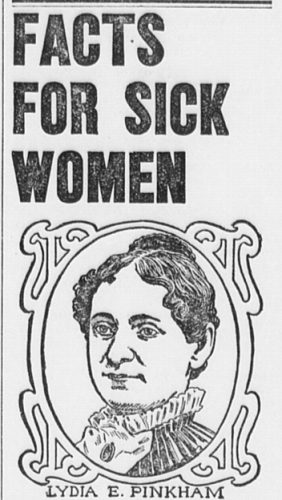

There were also a number of products developed to deal with “female complaints.” The most widely-known was Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. Her name and face were iconic, and even in 1948, there were still advertisements for her medicine in tablet form. Headaches, upset stomach, kidney disease, coughs, insomnia and dizziness were allegedly no match for these patent medications, and of course, some claimed to cure it all.

Lack of medical knowledge and government regulation allowed this industry to flourish, but not without devastating consequences. In addition to whatever natural ingredients the product may (or may not) have included, patent medicines typically incorporated opiates and alcohol. These may have reduced pain and alleviated other symptoms, but they were not particularly safe to ingest and could lead to addiction or even death.

After the real effects of these medicines were revealed through investigative journalism, the first Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906. Manufacturers had to print any ingredients defined by the law as “addictive” or “dangerous” on the labels (including alcohol, morphine, opium and cannabis) and engage in more truthful advertising. In 1938, this law was replaced by the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act which was even more restrictive, banning some ingredients altogether and requiring approval of the product by the Food and Drug Administration before going to market.

To see more patent medicine advertisements from historic newspapers, visit Chronicling America!

Thanks to Jenni Salamon, Unit Manager, Digitization, for this week’s post!

Further reading:

- Catarrh Remedy: Peruna Scandal, Topics in Chronicling America by Library of Congress

- “History of Patent Medicine” exhibit by Hagley Museum and Library

- Patent Medicines, Topics in Chronicling America by Library of Congress

- “Quack Cures and Self Remedies: Patent Medicine” exhibition by Digital Public Library of America

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.