Stories Told Through Craftsmanship and Fabric: Quilts on Ohio Memory

Hanging on my wall at home is what is known as an Underground Railroad quilt, pieced and quilted by my mother and her best friend. For those who are unfamiliar, Underground Railroad quilts are said to have contained messages for enslaved Black people who were escaping to the North in the 19th century. The presence of a quilt containing specific blocks supposedly indicated a safe house, a direction to take, or an action that would aid the escaping travelers on their quest.

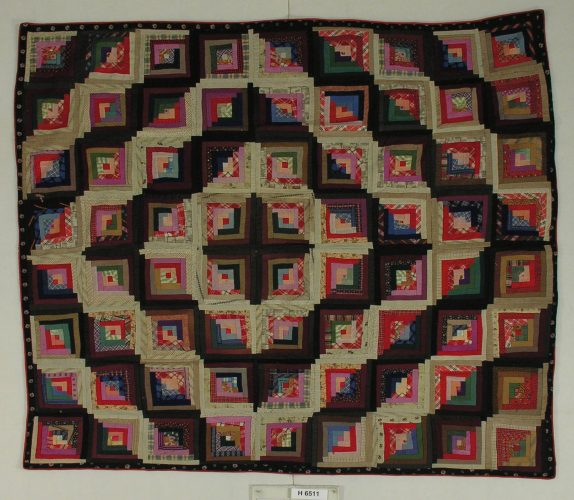

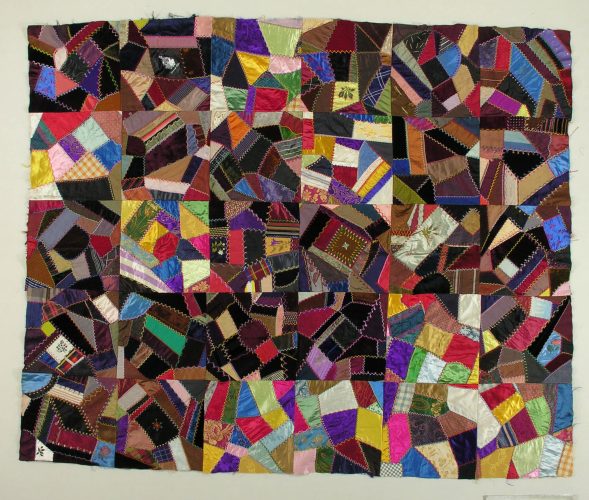

As it turns out, there is no evidence that quilts guided anyone to freedom and, instead, may be a myth that has taken on a life of its own, much like Betsy Ross sewing the first flag or George Washington and the cherry tree. That being said, every quilt tells a story, via blocks or fabric choices or workmanship (or, far more frequently, workwomanship). Today, we’ll look at the quilts on Ohio Memory and will see what stories they tell.

First, though, we need a quick lesson on quilts and quilting. Quilts consist of three layers: a top, which might be pieced or appliquéd, or a combination of the two, or it might be made of a single piece of cloth (called “whole cloth”); a middle, which adds warmth and creates the puffiness we associate with quilts; and a backing which, like the top, can either be pieced or whole (though it typically would not be appliquéd). The act of quilting involves creating a sandwich out of these three layers and stitching them together, often in a decorative fashion. All sewing can be done by hand or by machine.

Very early examples of quilts were made of whole cloth. These were also known as counterpanes or coverlets, and any decorative features would have been achieved via patterned quilting. The cloth may have been new (more on this in a moment) but, in this era before the industrial revolution, anyone who wasn’t wealthy was more likely to utilize items they already had. Such was the case with this coverlet, made from a quilted petticoat. Though we don’t know the maker’s name, we can see that she was skilled with a needle, that she was clever enough to repurpose something utilitarian and make it something lovely, and that she lived in a place that was cold enough to require a quilted petticoat. It’s still quite a story, despite the lack of identifying information.

As mentioned above, it was unusual for quilters to purchase yardage specifically for quilts. Hannah Aiken’s mid-19th century example is an exception: an appliquéd quilt using fabric that matches too well to be scraps. It’s possible, too, that the background fabric on which the pieces are appliquéd, was purchased new for this quilt. The high cost associated with creating a quilt like this tells us that this was made for a special occasion and by a skilled hand; no beginner would learn to quilt on such costly materials, nor would the materials be purchased to just be thrown on a bed. Compare this quilt to the second of Hannah Aiken’s quilts in Ohio Memory. This other quilt is made of patchwork, probably utilizing scraps left over from sewing garments or from garments that had worn out and could no longer be remade. This type of quilt is more utilitarian, probably made for frequent use. One can imagine Hannah guiding the hand of a small child who is learning to piece her first quilt, as the level of care taken with a patchwork quilt made from scraps simply isn’t the same as that taken with an heirloom like her appliquéd quilt. Both tell the story of love and care, however, in their beauty and in the fact that they were handed down for generations before they were donated by a descendant to the Shelby County Historical Society, a contributing member of Ohio Memory.

Additional quilts in Ohio Memory tell other stories: of a master quilter who enjoyed pushing herself to the best of her abilities; of a group of Quaker women who used quilting to express their abolitionist beliefs to their community; a woman who used a quilt to wish her granddaughter a merry Christmas; and yet another woman who used color and pattern to represent her love of home and family.

Feel free to check out these quilts and see what they tell you. And, then, take a look at your own treasured objects. What stories do they tell? Stop and listen to them and, then, write them down! And feel free to share them with us here at Ohio Memory. We would love to hear them!

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer-Trausch, Digital Initiatives Librarian at the State Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.