Learning and Labor: The History of Oberlin College

On December 3, 1833, twenty-nine men and fifteen women began classes at the newly established Oberlin Collegiate Institute in Oberlin, Ohio. This small beginning would grow into an institution that championed social justice and played an important role in integration and abolition in the years leading up to the Civil War.

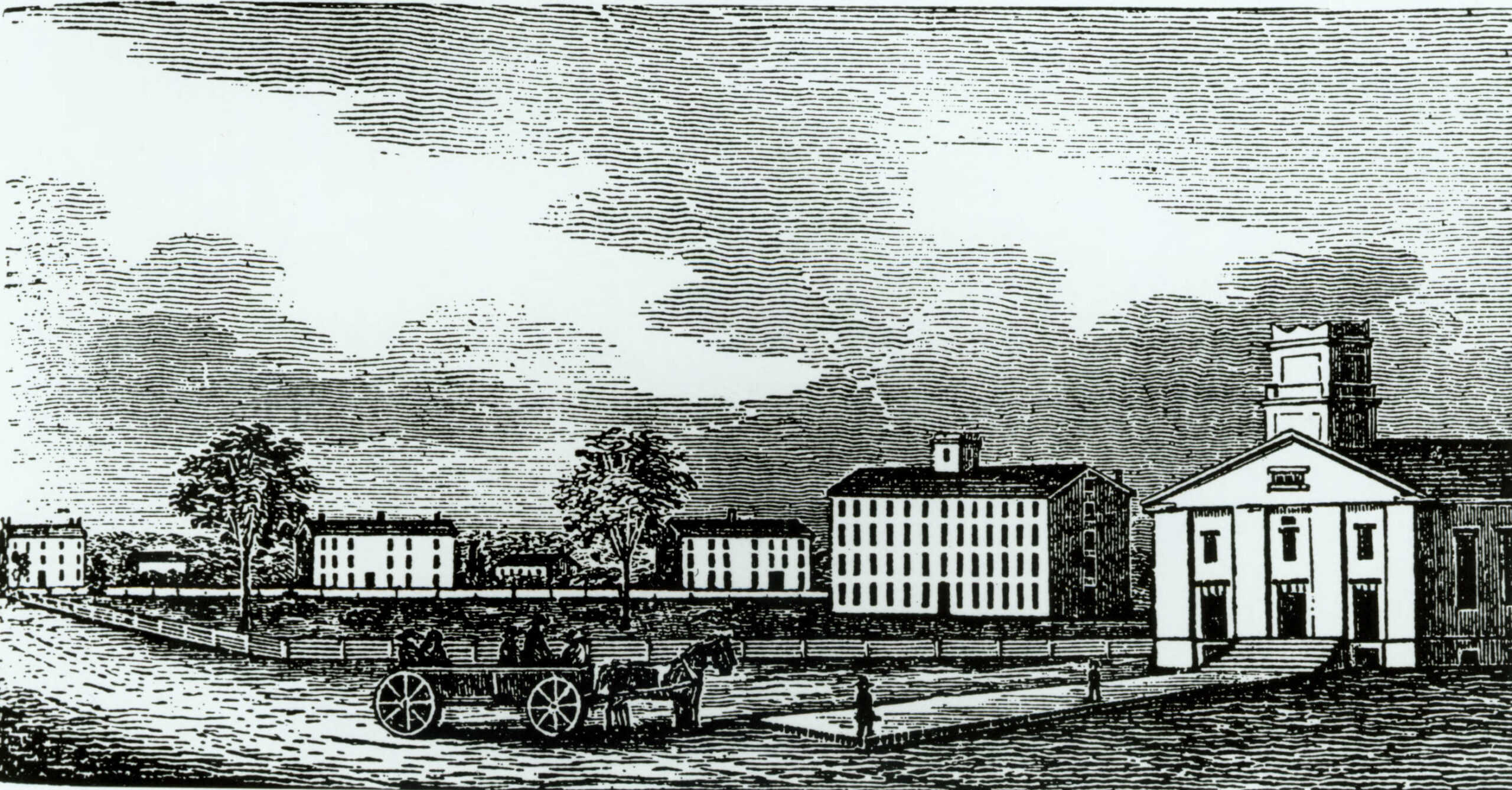

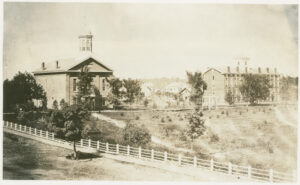

Oberlin was founded by Presbyterian minister John Shipherd and missionary Philo Stewart, with the help of wealthy benefactors that included New York City philanthropists and abolitionists Lewis and Arthur Tappan. The school was located on 500 acres of donated land in the Western Reserve, and was originally conceived as a plain-living community for training Christian missionaries and ministers. The school’s motto was “Learning and Labor”; tuition was free in the early years, but students were expected to help build and maintain the community. (This included literally building classrooms and dormitories.)

Oberlin didn’t admit Black students until 1835. The push for integration began when a large group of abolitionist students left Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati after the seminary prohibited discussions about slavery. The students, along with a trustee and a faculty member, agreed to join Oberlin but demanded integration as a condition for attending the fledgling college. The resolution–”That the education of the people of color is a matter of great interest and should be encouraged and sustained at the institution”–passed the board of trustees by a single vote. Despite the slim margin of victory, the decision made Oberlin one of the first few US colleges to admit African Americans and the first to admit people of color as an official policy. (Democrats in the Ohio General Assembly responded by trying to revoke Oberlin’s charter multiple times in the early 1840s.) By 1900, one-third of Black college graduates in the US were Oberlin alumni.

Oberlin was coeducational from the beginning, cementing its place as the oldest continuously operating coeducational liberal arts college in the US. However, early women students couldn’t earn bachelor’s degrees; instead, they received diplomas from the “Ladies Course.” Women first entered the bachelor’s program in 1837, and the first degrees were awarded in 1841, making Oberlin the first US college to award bachelor’s degrees to women in a coed program.

Without tuition revenue, finances were tight. John Shipherd made multiple fundraising trips to the eastern US while trustees William Dawes and John Keep (who cast the deciding vote to admit Black students) traveled to Britain, where they gave lectures about Oberlin everywhere from church halls to private homes. After eighteen months the trio raised $30,000, mostly from abolitionists–the equivalent of $640 million today. This money saved the school, and in 1850, the Oberlin Collegiate Institute changed its name to Oberlin College. This reflected a shift from the school’s original theology- and labor-based program to a more traditional liberal arts education.

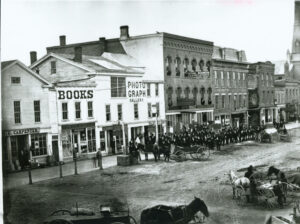

Although Oberlin’s anti-slavery reputation wasn’t shared by everyone in the area, the college and the community largely supported progressive ideas. Black residents attended church with their white neighbors, their children attended public school together, and Oberlin became a busy stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1858, residents of Oberlin and nearby Wellington, Ohio, freed John Price, an escaping enslaved man, from the custody of US marshals and escorted him to Canada in violation of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. After a federal grand jury indicted thirty-seven of Price’s rescuers, Ohio authorities responded by arresting the marshal and others who detained Price. Only two of the men indicted went to trial; although both were found guilty in federal court, their sentences were significantly lighter than the maximum allowed under the law. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue drew national attention, sparked a rally in which 10,000 people protested the guilty verdicts, and cost the chief justice of the Ohio Supreme Court the next election.

Oberlin students and faculty, along with local residents, continued their activism after the Civil War and into the next century. They campaigned for temperance and established the Ohio Anti-Saloon League, supported woman suffrage, and took part in the Civil Rights and women’s rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Today Oberlin College is home to nearly 3,000 students from across the US and nearly forty other countries. Happy Anniversary Oberlin!

Thank you to Stephanie Michaels, Research and Catalog Services Librarian at the State Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.