This Bizarre Case: The Scopes “Monkey” Trial

In 1925, the Tennessee legislature passed the Butler Act (linked below) which made teaching evolution a misdemeanor. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) immediately responded with an offer to any interested party: join them in challenging the Butler Act. 98 years ago this week, in Dayton, Tennessee, a local businessman, the high school superintendent, and a local lawyer saw this as an opportunity to bring fame to their town and recruited science teacher John Scopes as their partner.

Scopes, 24, wasn’t positive that he had taught evolution, but he admitted to using a textbook that supported evolution. This admission ensured his arrest, turning the conservative town of Dayton into the talk of the country. The Delaware, Ohio, Daily Journal-Herald, said that “the nerves of Dayton’s citizens are all aquiver with excitement and the heat waves that dance over its paved streets… Not that anybody has much interest in the actual cause at the bar, whether Mr. Scopes taught evolution in defiance of state law, or in what happens to him. He is a mere figure over which will joust the forces of science and religion, of fundamentalism and modernism, of liberalism and conservation.”

Further exciting the public were two of the lawyers litigating the case: William Jennings Bryant and Clarence Darrow. Both men were famous: Bryant had run for President three times and had built his reputation on being an anti-evolutionist and a fundamentalist Christian; and Darrow, an ACLU lawyer and agnostic who was born in Farmdale, Ohio, and grew up in nearby Kinsman, had just acted as defense in the sensational Leopold and Loeb murder trial. He was planning to retire but changed his mind when he heard of Bryan’s role in the Scopes case. In his autobiography, he said “My object, and my only object, was to focus the attention of the country on the program of Mr. Bryan and the other fundamentalists in America.”

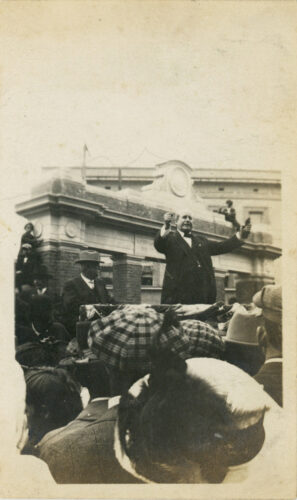

Darrow and Bryan were not above capitalizing sensationalism. Thus, on the seventh day of the trial, outside the courthouse and in front of a large audience, William Jennings Bryan agreed to be questioned as an expert witness on the topics of Christianity and knowledge of the Bible. Darrow proceeded to point out the inconsistencies in the Bible, while Bryan never wavered from his faith that the Bible was an accurate telling of events. The remarkable exchange can be read here, beginning on page 284.

Then came the eighth day. One can imagine that Bryan felt confident as he entered the courthouse. He had prepared questions for Darrow, expecting an opportunity to question him on his lack of faith, and had a closing argument ready. Then, to Bryan’s dismay, the judge ruled that his two-hour testimony was inadmissible. Darrow responded with a brief statement to the jury: “we have no witnesses to offer, no proof to offer on the issues that the court has laid down here… and I think to save time we will ask the court to… instruct the jury to find the defendant guilty.” He repeated the same to the jury, adding that only a case before the Supreme Court would yield justice. With that, Bryan’s opportunity for an examination of Darrow, and to present his closing statement, was gone. He told the judge, “I think it is hardly fair for them to bring into the limelight my views on religion and stand behind a dark lantern that throws light on other people, but conceals themselves,” and vowed to share his questions for Darrow with the press (this link to a site outside of Ohio Memory will take you to a transcript of the proceedings from the eighth day of the trial).

The jury did, indeed, find Scopes guilty, and the judge imposed the minimum fine of $100. When Darrow took the case to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, however, they dismissed it on a technicality: the jury, rather than the judge, should have set the fine. They followed this up by saying “we see nothing to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case” (see the Middle Tennessee State University’s “First Amendment Encyclopedia” page on the Scopes case).

Bryan died just five days after the end of the Scopes trial. After his death, his wife released his closing remarks so they could be published. In them, he argued that “the law did not have its origin in bigotry… it is trying to protect itself from the effort of an insolent minority to force irreligion upon the children under the guise of teaching science.” Darrow’s response was brief and concluded with “Today in Dayton they are selling more books of evolution than any other kind… the trial has at least started people to thinking.”

To learn more, click on these resources, all but one of which will take you to sites outside of Ohio Memory:

The Delaware Daily Journal-Herald offered extensive coverage of the trial, and you can read the relevant issues here in Ohio Memory: be sure to select only those articles from July, 1925

Read the Butler Act of 1925 here

California State University Dominguez Hills has a timeline, Bryan’s closing remarks, and Darrow’s brief response, here

Tennessee State Library and Archives shares information on the trial and its aftermath here

The University of Minnesota offers a large collection relating to Clarence Darrow and the Scopes Trial here Clarence Darrow digital collection, University of Minnesota:

You can find Clarence Darrow’s autobiography, The Story of My Life, here

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer-Trausch, Digital Initiatives Librarian at the State Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.