So Complicated an Investigation: The Electoral College

Every four years, with each U.S. presidential election, the Electoral College rises into prominence, becoming the subject of discussion and debate. This year, of course, is no different. Yet many of us lack a clear understanding of the purpose and function of the Electoral College. Who are the members? How do they operate within the electoral system? Is it still a necessary component of that system?

The Electoral College was first proposed by Alexander Hamilton in “The View of the Constitution of the President Continued in Relation to the Mode of Appointment” (Essay 68) of the Federalist Papers. In it, Hamilton argues that “the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided.” However, Hamilton was concerned that the voting population (at that time, entirely composed of white males) was not sufficiently equipped to determine the best man for the position. His solution: “the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station….” This group would be comprised of “a small number of persons, selected by their fellow citizens from the general mass…” as they would “be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to so complicated an investigation.” Through the utilization of electors, Hamilton believed that “the office of president will seldom fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

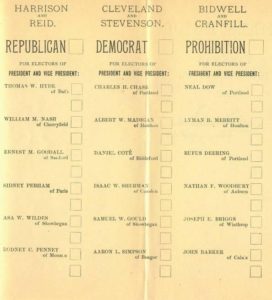

Under the U.S. Constitution, each state’s electors equal the number of representatives to U.S. Congress. Thus, Ohio has eighteen electors, one for each of 16 representatives plus our two senators. As with U.S. Representatives, the number of electors is based upon the population of each state; with the addition of senators, this number helps to balance powers between large and small states. Electors themselves are selected from prominent party members or are individuals who have made a considerable contribution in their respective states. The U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 2, decrees, however, that “no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.”

When we vote in a presidential election, we are actually voting for electors; that is, we are casting our ballots for specific electors who, in turn, will cast their electoral votes for president. In most states, the candidate who wins the majority of votes in a particular state receives all of that state’s electoral votes – this is the case in Ohio, as a matter of fact – but Maine and Nebraska have a system of representation that allocates electoral votes proportionally. In addition, the expectation is that electors will vote for the individual that won that state’s electoral vote. Those who do not do so are labeled “faithless electors” and face both censure from their party as well as a fine. Twenty-one states do not bind their electors to the candidate who has won the electoral votes for that state; Ohio, however, does bind electors to the winner, per Ohio Revised Code 3505.40: “A presidential elector elected at a general election or appointed pursuant to section3505.39of the Revised Code shall, when discharging the duties enjoined upon him by the constitution or laws of the United States, cast his electoral vote for the nominees for president and vice-president of the political party which certified him to the secretary of state as a presidential elector pursuant to law.”

Currently, 538 electoral votes are available for presidential candidates, who must receive a majority of 50% plus one – or 270 votes – to be considered the winner of the election. However, referring back to Hamilton’s argument that the electors must be a deliberative body, the “winner” is not awarded the votes until a later date; this year, that date is December 19. Electors will meet in their respective states on that date and will cast their votes for president. In the event that there is no majority winner, the choice of president is determined by the House of Representatives.

With the increased interest in the Electoral College after this year’s election, it can be challenging to find reliable sources of information regarding the system on the internet. We would like to share with you three documents that will give you an overview of the College: the Federalist Papers; a U.S. federal government document entitled Essays in Elections: The Electoral College; and a 1960 State of Ohio document from the Secretary of State entitled Your Electoral College and How It Works. We’ve also linked in the text above to an online version of the U.S. Constitution and to the National Archives and Records Administration, a federal government agency that retains, in perpetuity, materials relevant to American history.

Our system for electing a president is unique and unusual and, consequently, can be challenging to understand. It is, however, fascinating as well, and we hope that this very brief overview of the process sheds light on the system and captures your interest!

Thank you to Shannon Kupfer, Digital Initiatives Librarian at theState Library of Ohio, for this week’s post!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.